How does gender diversity improve science?

Men continue to outnumber women in science, technology, engineering and maths professions; what has been the effect of this predominantly male lens?

Published 14 August 2018

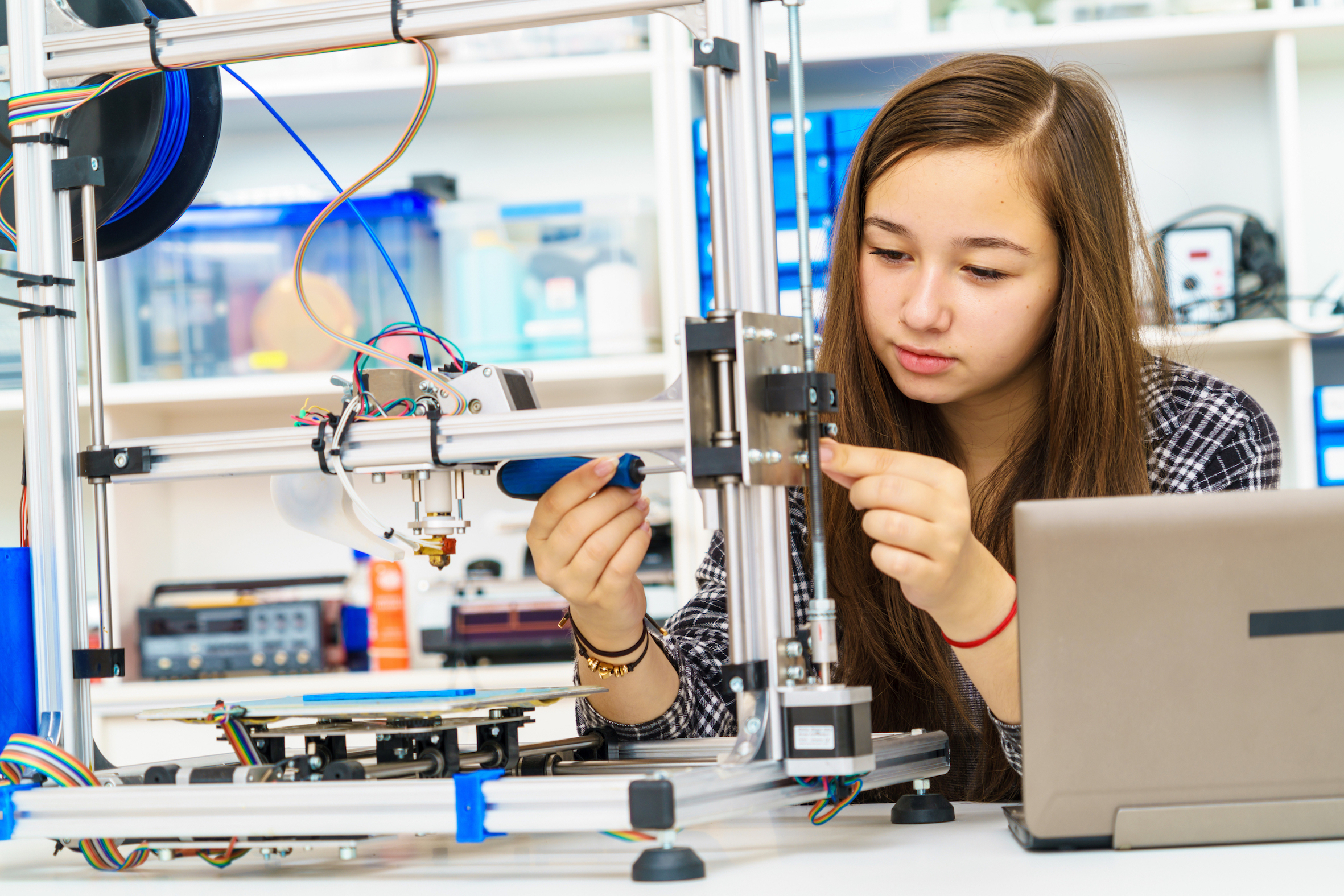

Science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM) are accepted as a furnace of innovation that can drive the growth of economies. Yet female participation in STEM careers globally, and in Australia, is low.

In Australia at school level, boys outnumber girls studying maths 2 to 1 – a ratio that has remained unchanged since 1991. Only 16 per cent of Australians in STEM professions are women. And where women do participate, there is a wide gender pay gap.

Why does gender matter when it comes to STEM research? And what can we do to improve female participation in disciplines deemed vital to the growth of our economies and society?

We tackle these issues with one of the world’s leading experts; Professor Londa Schiebinger.

Episode recorded: 9 August 2018 The Policy Shop producer: Eoin Hahessy Audio engineer: Gavin Nebauer

Research: Eugene Toh & Ruby Schwartz

Banner image: Pixababy

Subscribe to The Policy Shop through iTunes or RSS.

Subscribe to The Policy Shop through iTunes.