Indigenous astronomy

After moving from the US to study in Australia, astrophysicist Associate Professor Duane Hamacher now works to increase Indigenous representation in the astronomical and space sciences

Published 24 July 2019

Associate Professor Duane Hamacher has spent 11 years immersing himself in the world of Indigenous knowledge and Indigenous science.

Working closely with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Elders and communities to learn about their astronomical knowledge and teachings, Associate Professor Hamacher also mentors and supports Indigenous students pursuing studies in astronomy, physics and space science.

“I was very fortunate to be able to learn directly from many Elders,” says Associate Professor Hamacher.

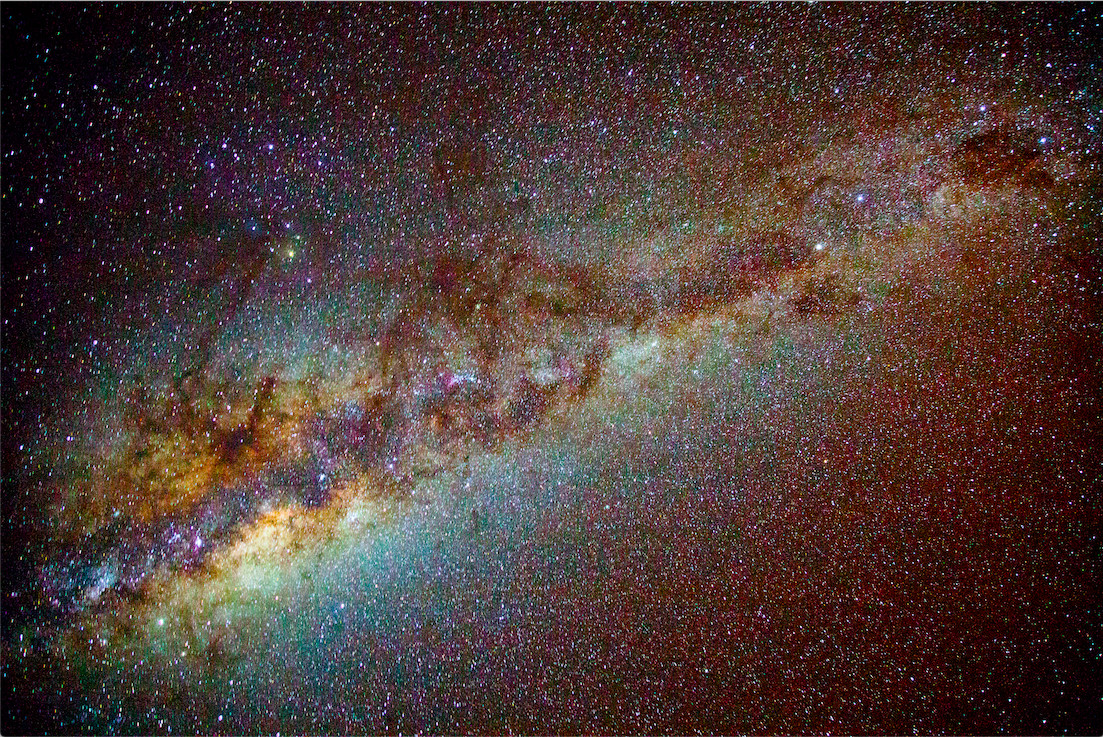

“The sky serves as a textbook, a logbook, a mnemonic a way of remembering. Everything on the earth, you can see in the sky.

“So, reading the stars means you can observe changes in their positions and properties and know how to interpret that to be able to tell things like changing weather or animal behaviour or navigation.”

He says we now have a whole new generation of Aboriginal students who are studying astrophysics and Indigenous astronomy.

“They are paving the way in this space to do something that I can’t do and people like me cannot do.”

Episode recorded: July 9, 2019.

Interviewer: Dr Andi Horvath.

Producer, audio engineer and editor: Chris Hatzis.

Co-producers: Silvi Vann-Wall and Dr Andi Horvath.

Image: Galactic Emu, Aboriginal astronomers mapped the sky by creating shapes from the dark clouds of dust in front of the centre of the Milky Way/ Shutterstock

Subscribe to Eavesdrop on Experts through iTunes.