Sciences & Technology

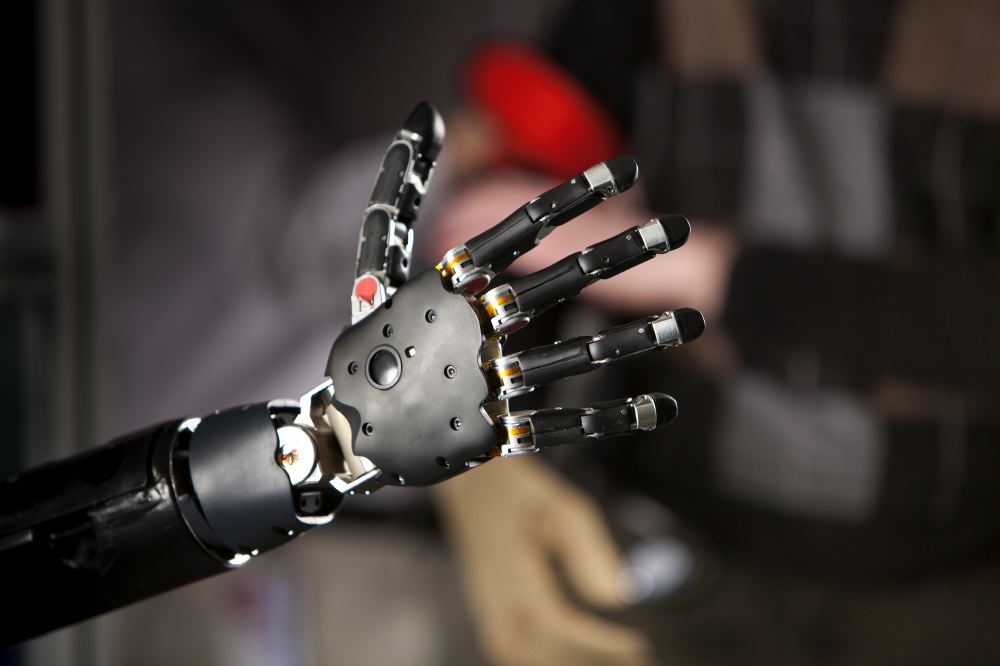

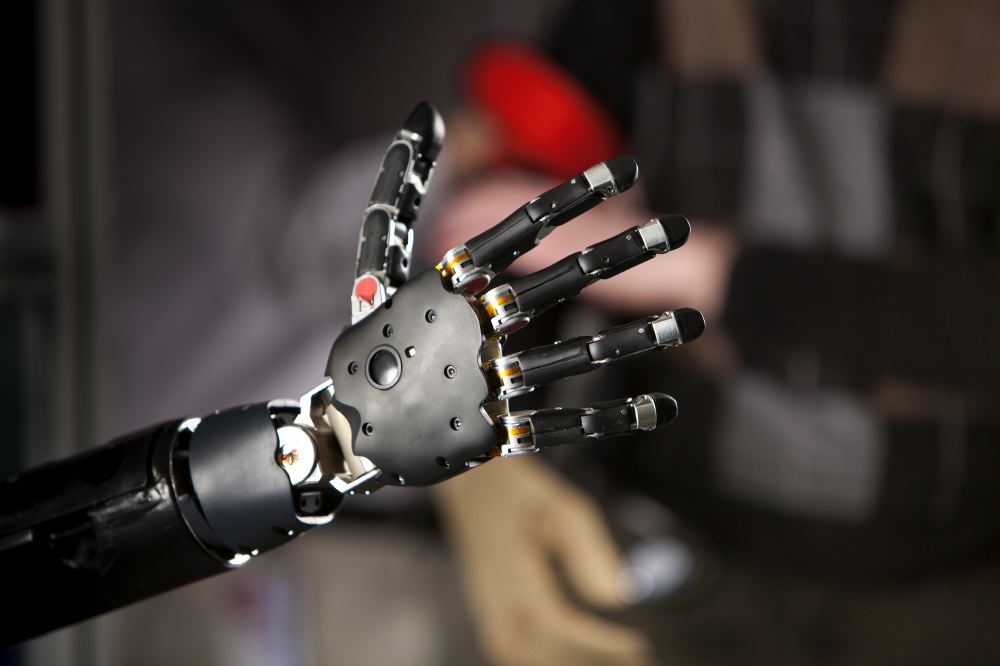

Rise of the robots

Richard Susskind argues professions are a relic from print-based society, and white collars workers like lawyers, consultants and accountants need to brace for change

Published 9 February 2018

The professions are being transformed by new technologies like artificial intelligence. Lawyers, academics, journalists, the medical professions and more are already seeing significant changes in their fields, and more is on the way.

Sciences & Technology

Rise of the robots

We already know robots are replacing many blue-collar jobs, but are the professions safe from the march of the machine?

Professor Richard Susskind discusses what the future might hold for our professions.

Episode recorded: 8 December 2017 Series Producer: Eoin Hahessy Audio engineer: Gavin Nebauer

Banner image: Pixababy

Subscribe to The Policy Shop through iTunes.