Arts & Culture

Life on the edge of the Great Sandy Desert

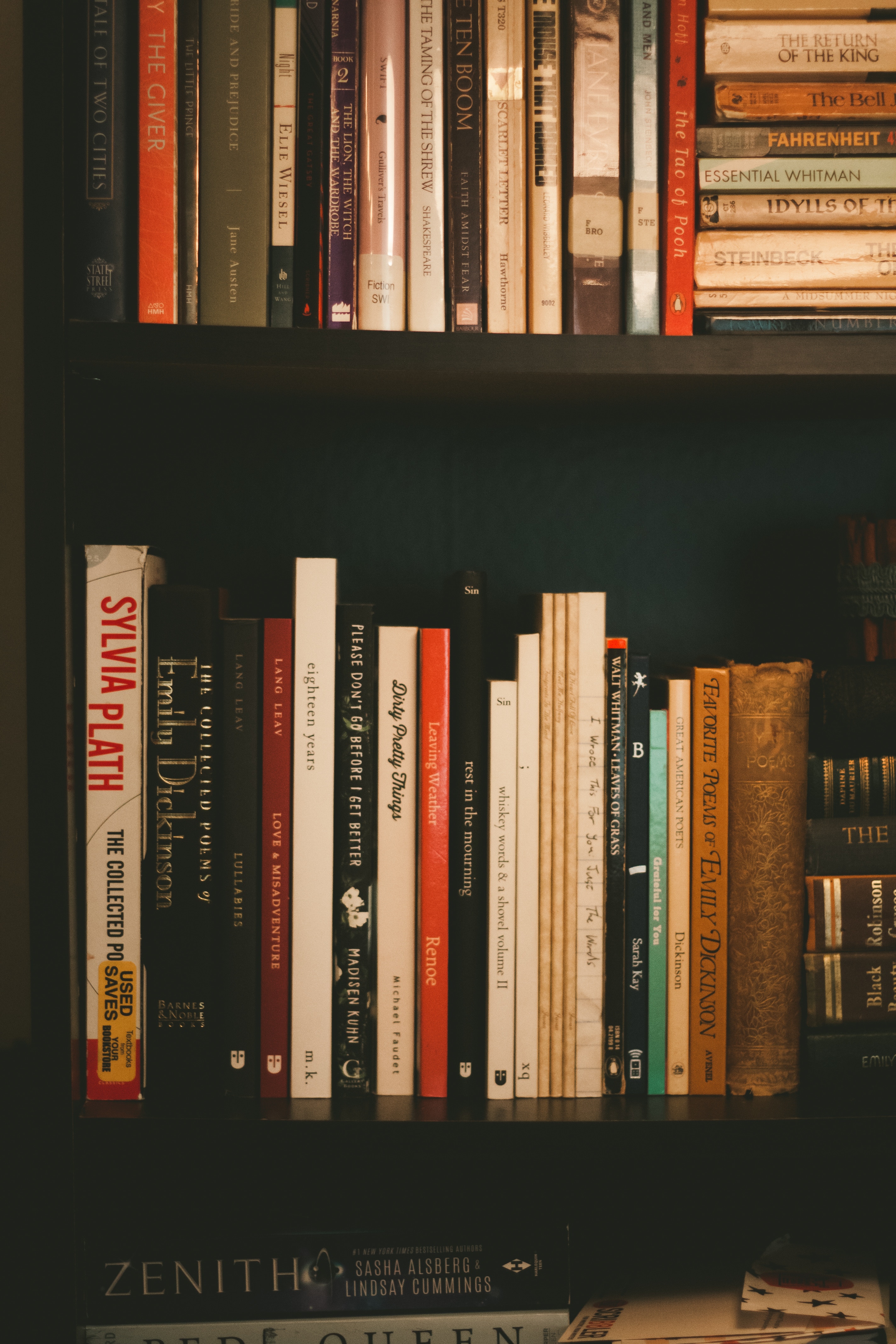

Poetry is a way of being alive and alert to the world in ways that we too often forget, says Professor David Mason

Published 7 November 2018

“Just being able to say beautiful words, to put beautiful words together, is a way of moving through time and living your life and holding onto your life more valuably.”

Arts & Culture

Life on the edge of the Great Sandy Desert

Professor David Mason, former Poet Laureate of Colorado, on why poetry is so ubiquitous and important.

Episode recorded: September 17, 2018

Interviewer: Dr Andi Horvath

Producer and editor: Chris Hatzis

Co-production: Dr Andi Horvath and Silvi Vann-Wall

Banner image: Taylor Ann Wright

Subscribe to Eavesdrop on Experts through iTunes.