Business & Economics

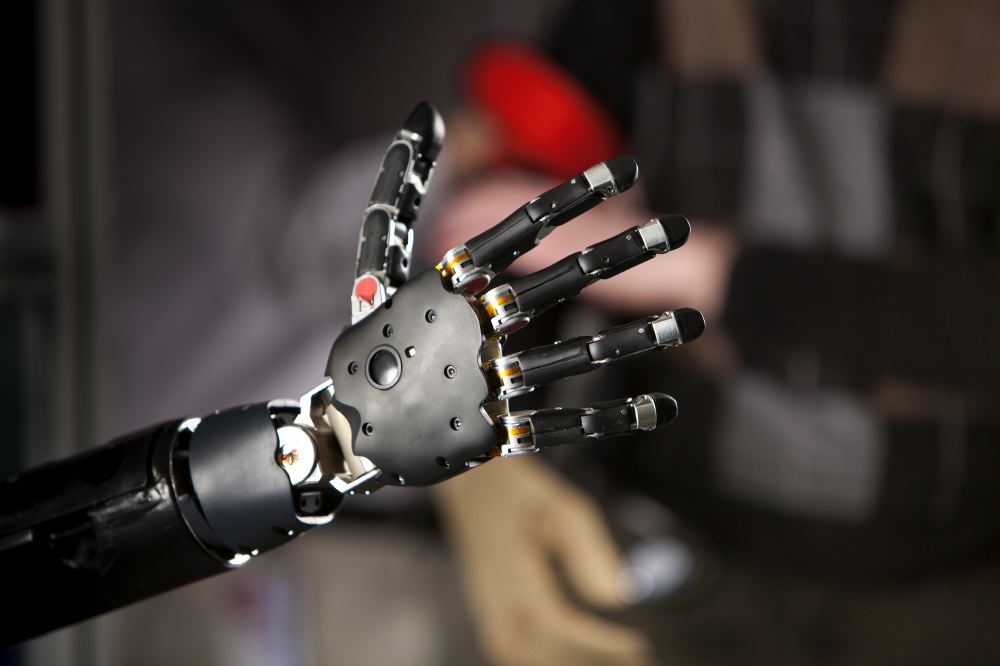

Will a robot take your job?

More than half of all existing jobs will be automated within 20 years - but is this a threat or an opportunity?

Published 5 September 2017

The world of work is changing - fast.

Economists predict that in the coming years, many traditional jobs and trades will be rendered obsolete as a result of automation and robotics.

Business & Economics

Will a robot take your job?

Estimates show that around 45 per cent of workers currently perform tasks that could be automated in the near future. As the trend gathers pace, more than half of all existing jobs will be automated within 20 years.

For Australia, this means up to 5 million jobs lost.

To discuss what the future of work might look like, former economic advisor to President Bush and President Obama and co-founder of H-Robotics, Dr Pippa Malmgren, and former advisor to the Prime Minister and director of AlphaBeta consultancy, Dr Andrew Charlton join the host, Professor Glyn Davis, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Melbourne.

Episode recorded: 16 August 2017 The Policy Shop producers: Ruby Schwartz and Eoin Hahessy Audio engineer: Gavin Nebauer

Banner image: Wikimedia Commons/The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHU/APL)

Subscribe to The Policy Shop through iTunes.