Education

Daring to learn how to learn

As students prepare for their end-of-year exams, new research is exploring an alternative to the ATAR that may better recognise student achievement and inspire good learning

Published 29 October 2019

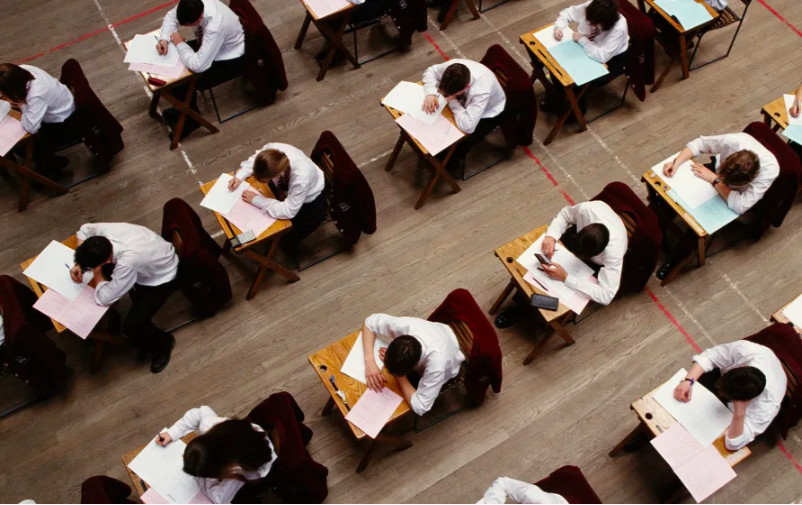

As the name may suggest, the Australian Tertiary Admissions Rank (ATAR) is uniquely Australian.

Internationally, our school system is alone in using a single number, from zero to 99.95, to rank every school leaver looking for a place in tertiary education.

This ranking, which indicates a student’s performance relative to their peers, is used to distinguish between students vying for entry into competitive tertiary courses.

But is this the best way to capture twelve years of achievements by our young people? Does it adequately capture what they know and can do? Does it inspire and support good learning? Is it still fit for purpose a decade after its introduction?

Education

Daring to learn how to learn

The system is cutthroat and intensely competitive.

A candidate with a rank of 85.5 might get into their university course of choice. But someone with a rank 85.45 – the same score for all practical purposes – who has a subject history and passion much more aligned to the course, does not.

It has a powerful, universal influence on parents, teachers, and young people navigating the transition from schooling to post-school life.

But for all its well documented faults, the ATAR is often supported because it is fair.

That is to say, everyone operates under the same handicap, it measures something relevant to higher education study, and the score is not easily fudged.

However, our new report by the Australian Learning Lecture says that there is a better way, with benefits for everyone.

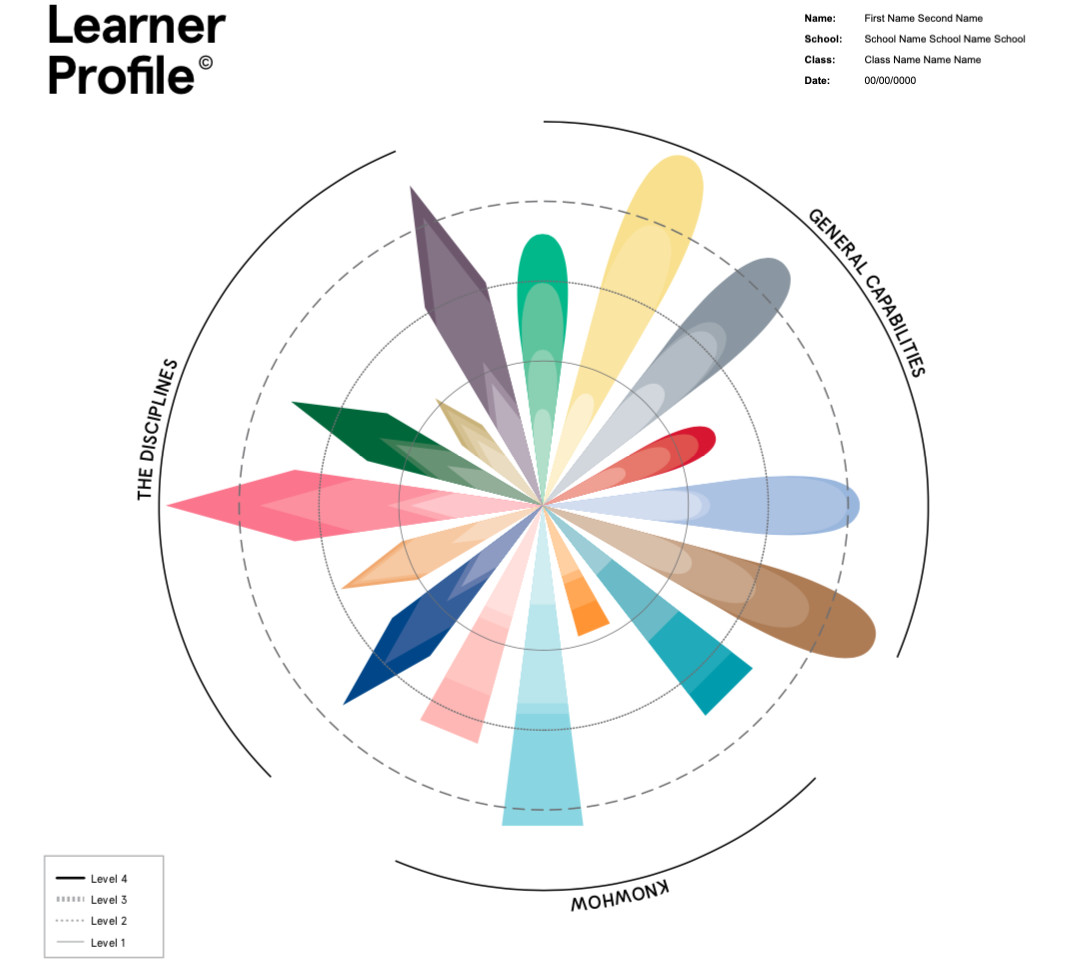

The report, Beyond ATAR: a proposal for change, proposes use of a document known as a ‘learner profile’ to replace or supplement simple numerical results such as the ATAR, for all young Australian aged 15 to 19 years.

A learner profile could be a way to provide a rich and detailed summary of what a student has learned, which is both flexible but enables comparison between students.

Using evidence from the learner’s time in school, it would showcase their strengths, passions, patterns of capability and attainments.

Business & Economics

Why ATAR averages are poor measures of school performance

Their strengths in particular areas can be highlighted, whether its maths, literature, hospitality skills, entrepreneurship or caring.

The learner profile could broaden what is counted as school success which, at the moment, is constrained by systems like ATAR that only capture knowledge skills of the type that can easily be learned in classrooms and tested in exams.

There is currently little visibility of the development of general capabilities, or qualities such as know-how, a good attitude or self-reliance.

But these are all qualities now advocated by curriculum experts and sought by recruiters, and selectors who want a more sensitive way to match candidates to opportunities in their organisations.

A central idea of a learner profile is the accumulation of ‘warranted micro-credentials’, or small chunks of learning that are guaranteed by an authority who shows that the holder has actually demonstrated the relevant qualities or attainments.

A micro-credential might recognise an achievement in a school certificate or vocational subject, or a recognised community service or an award in computer programming earned in out-of-school activities.

Because they accumulate over time, they add up to a full representation of the attainments, passion and purposes of a person.

This way of building a profile has other advantages.

For a start, it can take into account skills learned in places other than the classroom, like work experience or in alternative programs like Big Picture schools or Hands on Learning.

Many students already learn in these ways, but their attainments are currently unrecognised.

Most importantly, a developmentally based learner profile, built up over time, will empower learners in a way that an ATAR score cannot.

A learner profile can accommodate the fact that people learn gradually, over time, in fits and starts, after effort and commitment.

Young people should be able to improve through further effort, pivot if they have made a poor choice or if circumstances change, and be able to represent their best selves, regardless of background or opportunity.

Designing a learner profile for Australian learners will be no simple task.

We need to understand that what the profile should look like, and that will depend on what learning is valued by society and how we assess and recognise learning.

We will need to involve students, recruiters and selectors in the co-creation of the profile to make sure it is better than the ATAR at representing the knowledge, skills and capabilities that young people need to thrive in a modern world.

But perhaps the most important consideration is that the profile will only be trusted to the degree that the micro credentials that make them up are trusted and based on good assessments which reflect real competence.

ATAR scores and their predecessor have persisted for decades precisely because they are widely trusted.

This trust is based on a well-oiled, centralised organisations which ensures that the assessments are comparable, reliable, interpretable and precise.

These systems depend on standardisation and uniformity which usually demands young people spend two years sitting in instructional classes, regardless of how they learn best, or how that long mastery might take.

To this end, the Assessment Research Centre has worked with a range of pioneering partners to develop the technologies and techniques needed to create trusted learner profiles.

The process has required careful consideration of how we can represent attainment with high-quality assessments within the complex web of existing regulatory standards; and how we can instil confidence in the system by protecting it from gaming, misrepresentation and bias from those with privileged access to opportunity.

Designing and implementing a learner profile for Australia which lives up to these ambitions will require political will and buy-in from not only state territory governments, but from all potential users of the profile: students, recruiters, selectors, businesses, and teachers.

A range of reviews and enquiries is currently underway or reporting – which could set change in motion. The positive response from our report suggests that the idea of the learner profile for all young people seems to have promise.

A system which more accurately reflects student achievement and captures their breadth and depth of learning could pave the way for a more equitable future as young people navigate life after high school.

Banner: Getty Images