Business & Economics

COVID-19’s ongoing supply chain chaos

Australia can’t rely on industry and charities to feed people during disasters - government must lead in food security

Published 4 March 2022

Australia is currently facing another “unprecedented” weather event with extreme flooding in Queensland and New South Wales. And thousands of people in flood-affected areas are feeling the impacts of the floods on their lives, including their access to food.

Stores are running short of fresh food in parts of northern NSW and Queensland, and the major supermarkets have introduced buying limits on some foods in flood-affected areas.

Empty supermarket shelves and temporary food shortages are becoming more common in Australia, due to disruptions in food supply related to the COVID-19 pandemic and extreme weather events.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has warned that extreme weather events – like floods, heatwaves, fires and droughts – will become more frequent and more severe in Australia due to climate change.

And this is likely to lead to more frequent disruptions to food supplies and rising food prices.

Business & Economics

COVID-19’s ongoing supply chain chaos

Governments in Australia currently rely mainly on the food industry to shore up the resilience of food supply chains to disasters and on charities to ensure that people are fed through emergency food relief.

This isn’t an adequate response. We need more government leadership to strengthen the resilience of our food supply chains to the very likely future shocks.

Climate and pandemic shocks have impacts throughout our food system – from production to consumption. The recent flooding on Australia’s east coast has inundated vegetable crops in low lying areas of the Lockyer Valley near Brisbane, an important area of horticultural production.

Fresh food supplies have been damaged in warehouses and the Brisbane Markets is closed as a result of flood damage.

On top of this, the Pacific Highway between Sydney and Brisbane is blocked in places, disrupting the distribution of food to some supermarkets, and emergency food supplies are being provided to flood-affected residents.

We’re also likely to see an increase in food waste due to crop losses, delays in food freight and power outages.

Shocks like floods and the COVID-19 pandemic can affect a large number of people through temporary food shortages and rising food prices. But they have the greatest impacts on people already at risk of food insecurity.

Rates of food insecurity in Australia are highest among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, asylum seekers, people who are unemployed and low-income households.

During the first 12 months of the COVID-19 pandemic, demand for food relief in Australia doubled. More people were pushed into food insecurity, including casual workers who lost jobs, temporary migrant workers and international students.

A year later, in 2021, around one in six Australian adults were severely food insecure and 1.2 million children were estimated to be living in food-insecure households. But demand for food relief in Australia had been rising even before the pandemic. This points to more systemic causes, such as low levels of income support.

Governments around Australia must develop plans to increase the resilience of food systems to shocks and stresses.

While some governments typically have plans to manage emergency food supplies during a disaster, they must also focus on actions that build the long-term resilience of food systems to a range of future shocks linked to climate change, pandemic and geopolitical shifts.

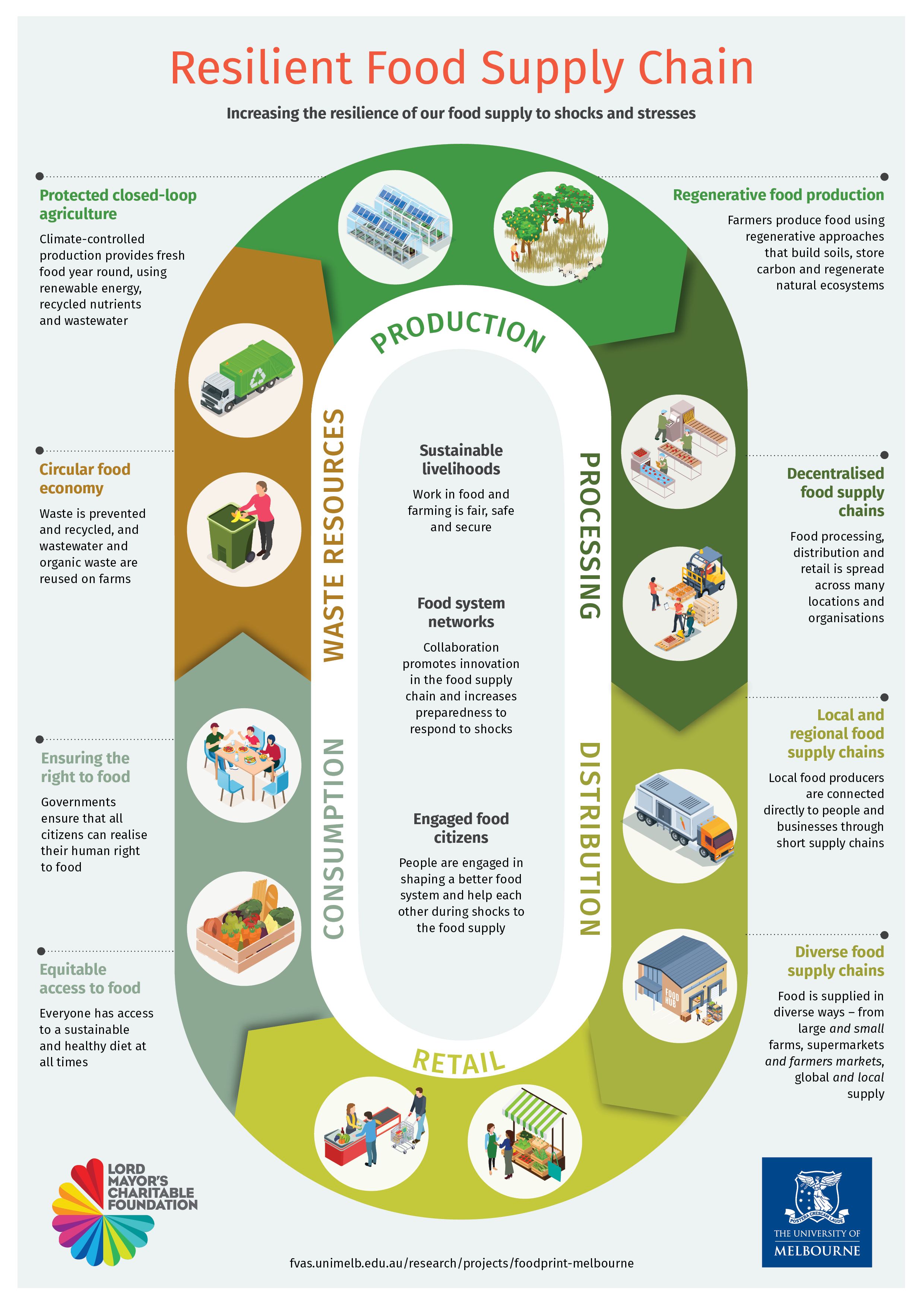

Our research into the resilience of Melbourne’s food system identifies some key features of a resilient food system. One key area worth exploring is the diversity of where and how we source our food – global and local, large and small scale, commercial and community enterprises, supermarkets and other food markets.

The COVID-19 pandemic has already highlighted the risks of highly centralised food processing and distribution.

So, another important focus area is the decentralisation of our food supply chains. This would mean food processing, distribution and retail are spread across many locations and organisations.

Business & Economics

Encouraging responsible sourcing in our supply chains

We also need to strengthen local and regional food supply chains. Short food supply chains that connect people directly to sources of locally produced food can increase the resilience of food systems when longer food supply chains are disrupted, as well as build up local economies.

There is a common belief that Australia is a food secure country because we produce and export a lot of food.

But food security is about more than the amount of food that we produce. It’s also about ensuring equitable access to nutritious food and ensuring the resilience of food supplies in the face of shocks and stresses.

Australian governments need to develop food resilience plans that outline how they will ensure that all Australians have access to enough nutritious food in a world that’s going to see increasing shocks to food supplies in the future.

This article was co-published with The Conversation.

Banner: Getty Images