Arts & Culture

Putting museum power on the map

As library, museum and other heritage collections go online, we need to consider who is creating these collections and why

Published 29 January 2024

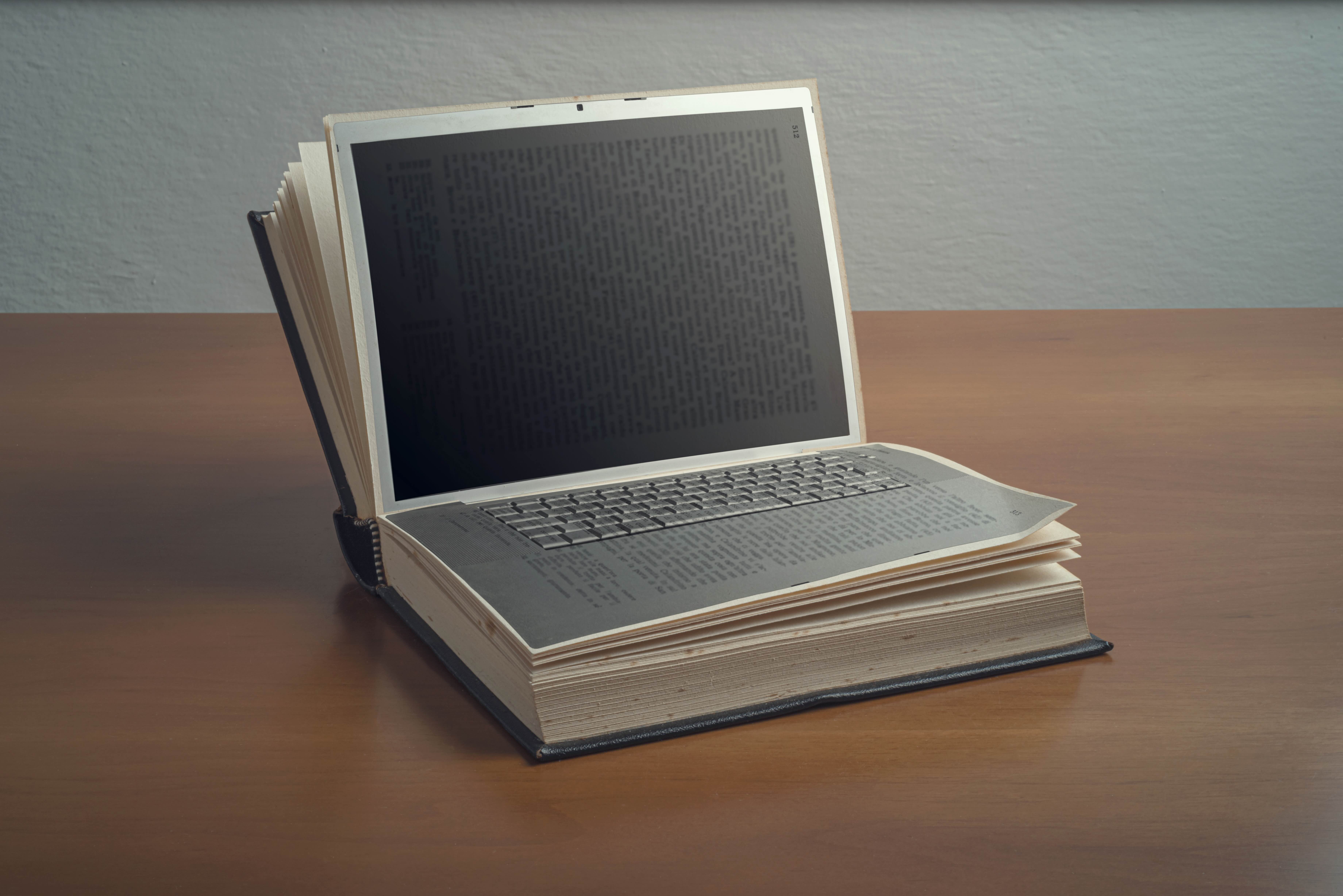

The idea of creating a ‘universal library’ which contains the entirety of all the human knowledge and heritage has inspired the imaginations of the brightest minds of scholars and humanists since ancient times.

A good example is the Library of Alexandria – the most famous library of classical antiquity in Egypt from the early 3rd century BC. It aspired to contain a copy of every book ever written or translated and its bibliography long remained a standard reference work until its destruction during a civil war in 48 BC.

In the 21st century, the development of digital technologies and the internet has given us technologies to protect our heritage from material loss and destruction. Furthermore, they enabled a global hyperconnected network of knowledge that transcends cultural, linguistic and geographic boundaries.

Not surprisingly, there are now many grand projects that aspire to bring together our human shared heritage into a single space, existing in a virtual reality.

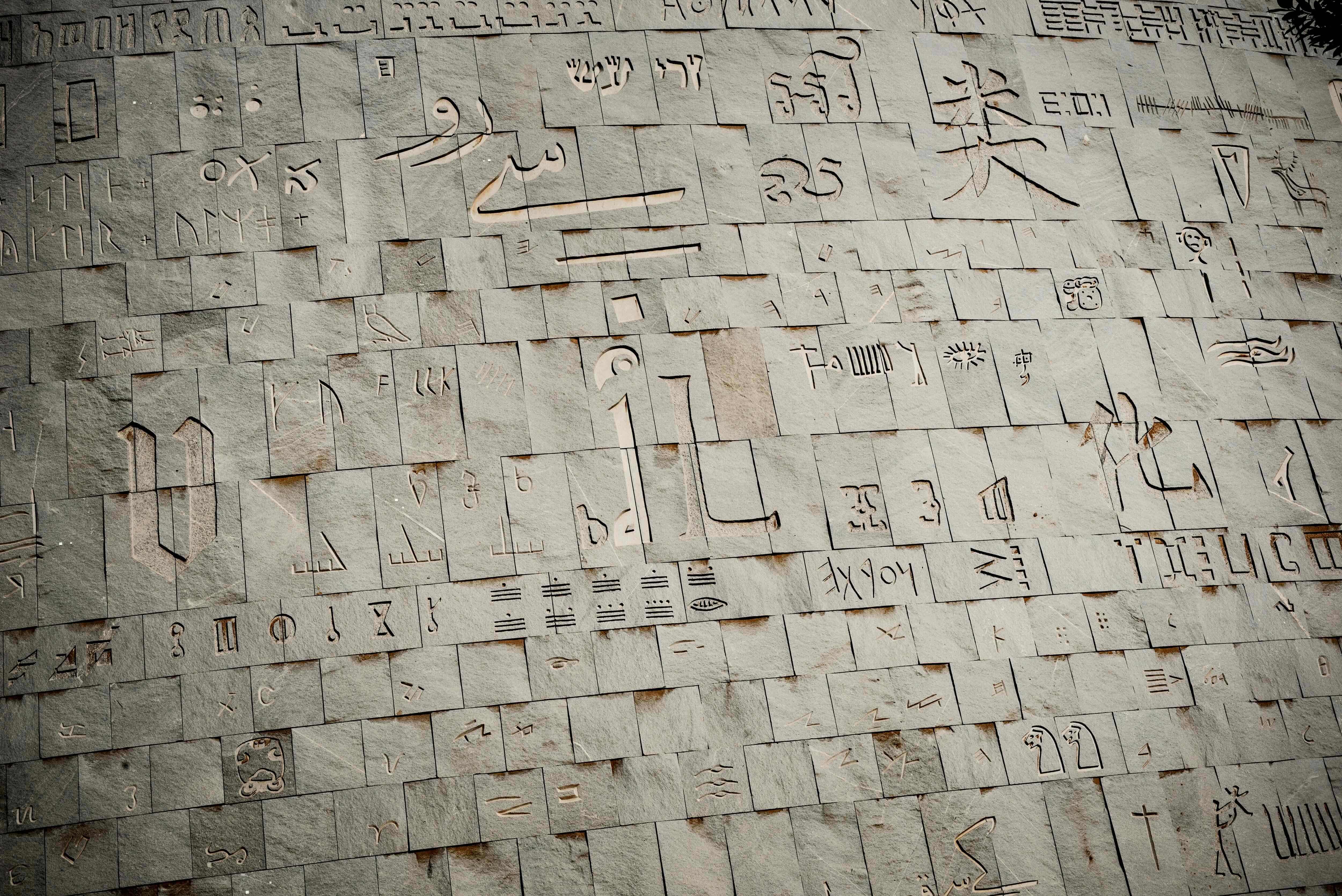

The exponential growth of technologies that digitise content means human heritage can be easily captured, stored and globally shared in a wide variety of formats, from mere texts to music, images, videos and interactive multimedia installations.

Arts & Culture

Putting museum power on the map

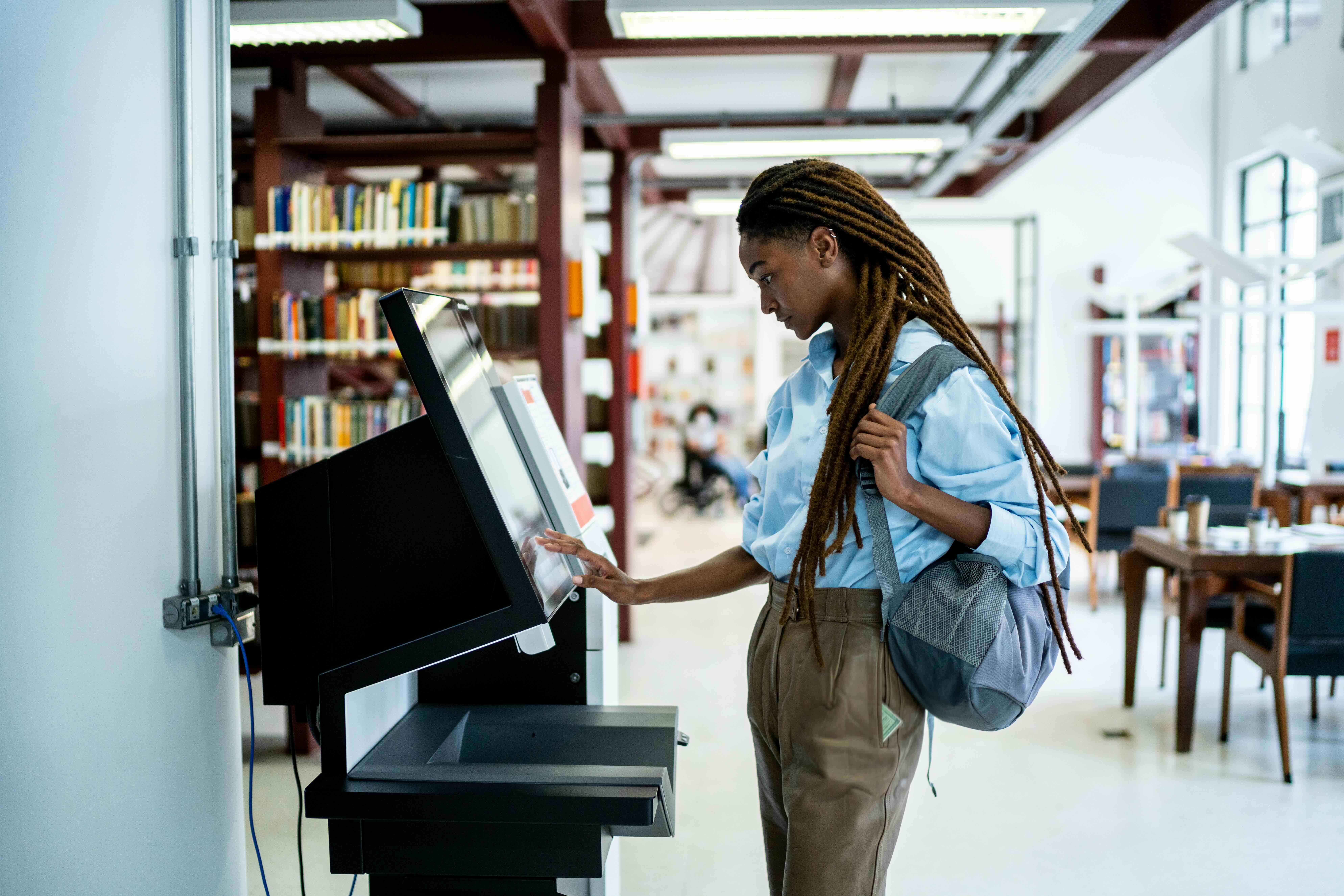

This has given birth to so-called digital heritage aggregators – large-scale virtual libraries that collect, format and manage collection data from different heritage institutions to create a single access point via an online portal.

There are no limits to the size or geographical scope of the heritage collections – from local collections to ambitious global projects.

For example, the National Library of Australia developed Trove, which it says “brings together billions of pieces of information”, giving everyone free access to “amazing collections from Australian libraries, universities, museums, galleries and archives”.

Similarly, the European Union (EU) funded Europeana which displays digital cultural heritage from over 2,000 cultural institutions, in dozens of different languages, covering the whole EU and beyond.

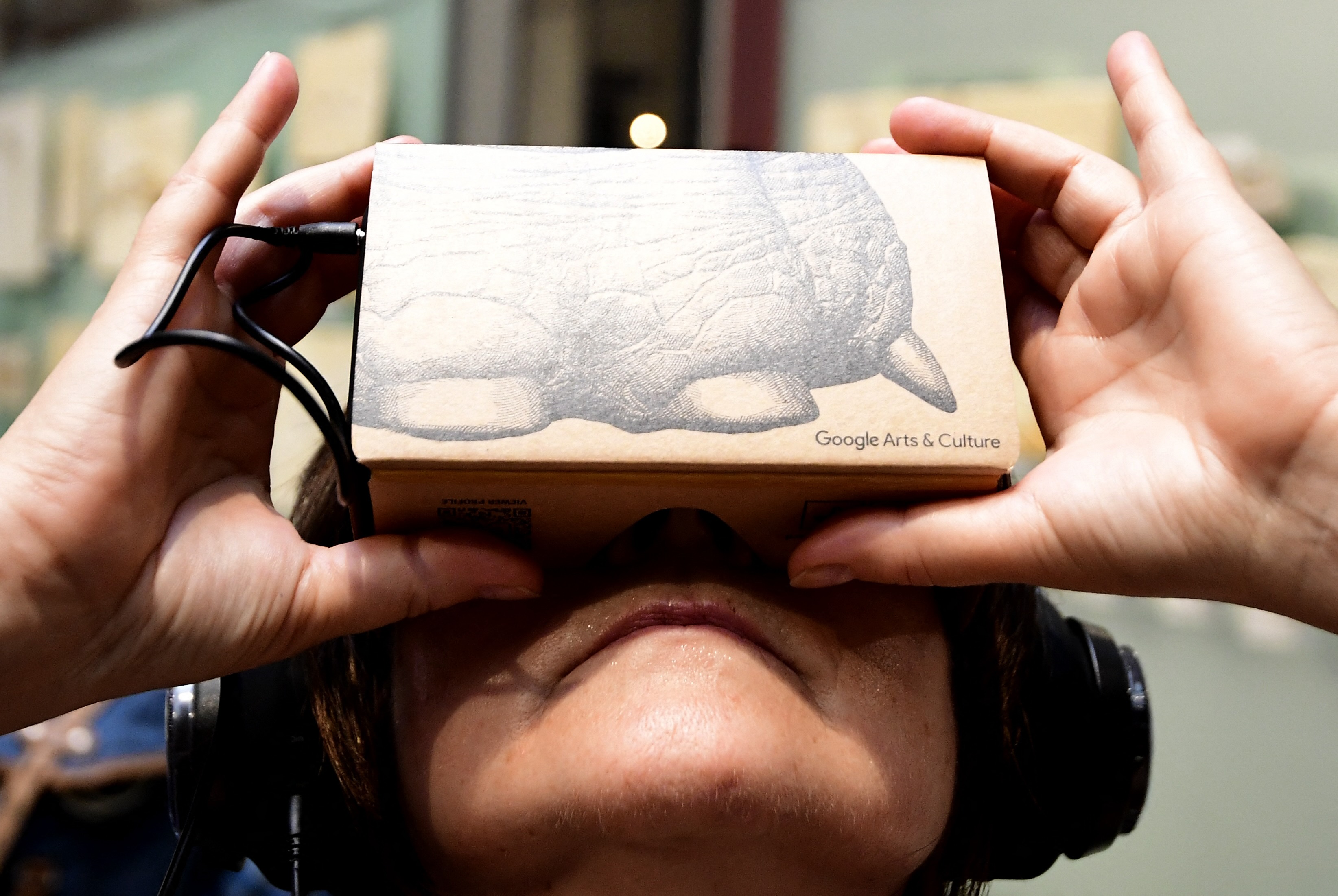

An even greater ambition for a true ‘universal library’ that aims to bring all human heritage together is the Google Arts and Culture project, which aspires to “bring the world’s art and culture online so it’s accessible to anyone, anywhere.”

Although not truly ‘global’ – the project currently collaborates with just 2,000 cultural institutes in 80 countries – the COVID-19 pandemic elevated its global popularity, as it provided a way to visit places and collections that were otherwise inaccessible.

Digital heritage aggregators promise to realise long-lived dreams for a universal library with the help of rapidly upscaling technologies, which now also include the metaverse for immersive heritage experiences, and AI that enhances human heritage preservation and sharing.

Arts & Culture

Museums in cyberspace

However, we should not ignore the lessons from our history. Previous attempts to create universal libraries have failed spectacularly.

The accumulation, preservation and (more importantly) the display and circulation of digital heritage is hugely resource demanding and highly expensive exercise.

Only certain wealthy states like Australia, intergovernmental political entities like the EU, or the largest transnational media corporations in the world, like Google, may be able – or willing – to pay this cost.

This is an issue, because heritage preservation activities to sustain these large-scale ‘history machines’ are never politically neutral and, in fact, come with their geopolitical ambitions diving their investments.

Geopolitics is also as old as the history of humanity; it is a competition among world actors to control people, places and ideas for political or economic advantage – or even to pursue global domination.

However, in the digital era, this power does not necessarily sit with military might, but rather depends on digital infrastructures and the capacity to ‘globalise’ technological systems to shape international standards, products, rules and even social norms and cultural values.

Digital geopolitics is a more sophisticated game to shape global informational environments, mobilise online communities and control cultural representations to influence our values and identities.

Arts & Culture

Translating data into soft power

Not surprisingly, digital heritage aggregators are quite effective geopolitical tools.

The immense storytelling abilities of our digital heritage make aggregators highly political – especially when these stories concern cultural and political borders, contested territories and cross-cultural communication issues.

Geopolitics is not disconnected from everyday life: “the actions you take, and the way you respond to events, matter in terms of their geopolitical outcomes.”

My new book, Geopolitics of Digital Heritage, written with Dr Liz Stainforth from the University of Leeds, explores how politics manifests in the development of digital heritage platforms to serve different actors, ranging from national governments to transnational corporations, in their geopolitical competition for human attention and the power to control our thoughts and feelings.

In it, we explore questions like: Is browsing Trove materials that aspire to project the national Australian identity a geopolitical act? And if we connect to this projection, what does it mean if our marginalised cultures, be it First Nations Australians or immigrants from emerging economies, are missing from the grand narratives of the aggregator?

Similarly, do EU citizens get a chance to taste the real ‘European culture’ when they explore the millions of objects in the Europeana collections and how do the ‘borders’ of these heritage treasures different from the EU legal borders?

And then there’s Google.

Arts & Culture

Treading softly in power diplomacy

Does it matter if it tracks our digital paths to generate income every time we click to virtually visit a museum, explore a digital exhibition, or enjoy a cultural tour to an exotic destination on its Arts and Culture platform?

Are we victims of human heritage politization and commodification on behalf of governments and transnational corporations seeking global media domination, or do these digital pathways allow us to discover who we are by traversing the human heritage on the Internet?

Having an awareness of those writing the history of humanity and shaping our memories is the first step to navigating heritage geopolitics.

The next step is to claim our right to participate in creating our own heritage platforms, spaces and communities and letting the ancient dream of a ‘universal library’ be a good history lesson for generations to come.

The monograph, Geopolitics of Digital Heritage, is in free Open Access until 4 February 2024.

Banner: Getty Images