Farmed salmon hard of hearing

A surprising discovery has implications for fish farming and fish conservation programs

Published 28 April 2016

Half of the world’s farmed Atlantic salmon have deformed earbones and as a result, poorer hearing, new research has revealed.

It’s a finding that raises new questions about the welfare of farmed fish — particularly the billion of Atlantic salmon harvested each year — as well as the survival of captive-bred fish that are eventually released into the wild.

University of Melbourne researchers discovered half of the world’s most farmed marine fish, Atlantic salmon, have a deformity of the otolith or ‘fish earbone’.

Otoliths are located behind a fish’s brain and are essential for hearing and balance, much like the inner ears of humans and other mammals.

Ms Tormey Reimer, from the University of Melbourne’s School of BioSciences, led the study, which has been published in the journal Scientific Reports.

“Farmed fish are 10 times more likely to have the earbone deformity than wild fish, ” Ms Reimer said.

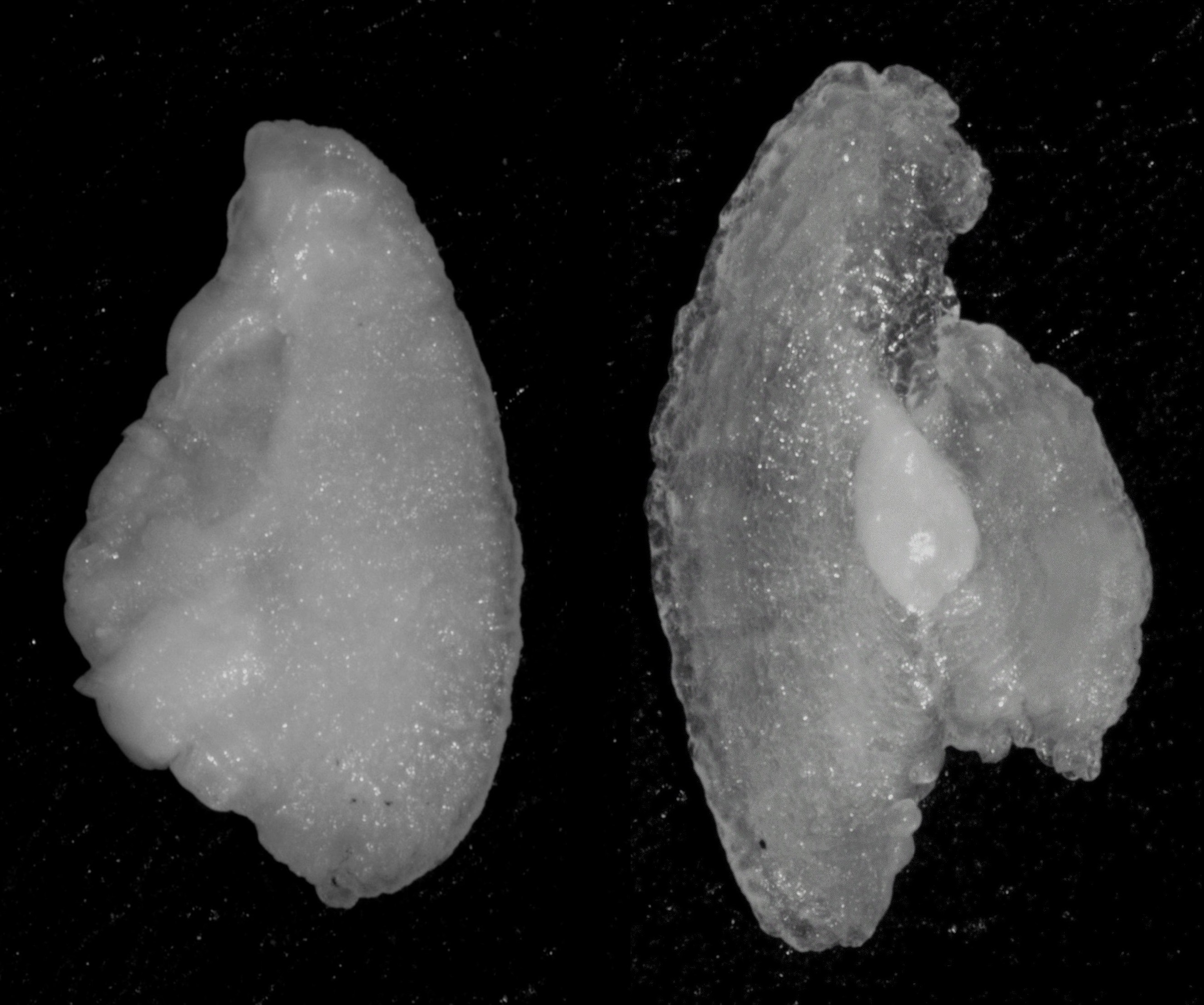

The deformity occurs when the typical structure of calcium carbonate in the fish earbone is replaced with a different crystal form. The deformed earbones are larger, lighter and more brittle, and the way they perform within the ear changes.

The deformity is very uncommon in wild fish.

“It occurs at an early age, most often when fish are in a hatchery, but its effects on hearing become increasingly more severe as the fish age,” Ms Reimer says.

“Our research suggests that fish afflicted with this deformity can lose up to 50 per cent of their hearing sensitivity.”

To test if the deformity was a global phenomenon, researchers from the University of Melbourne and the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research sampled salmon from the world’s major salmon-producing nations: Norway, Canada, Scotland, Chile and Australia.

The team compared the structure of the otoliths from farmed and wild salmon. They also compared the hearing of the fish using a model that predicts what a fish can hear.

Regardless of the country where salmon were farmed, the deformity and subsequent hearing loss occurred at much higher rates in farmed fish than wild fish.

“Something about the farming process is causing the deformity,” says co-author Associate Professor Tim Dempster from the School of BioSciences, University of Melbourne.

“We now need to work out what is the root cause to help the global salmon industry produce fish with acceptable welfare standards.”

Over two million tonnes of farmed salmon are produced worldwide every year, with more than a billion fish harvested.

“We estimate that roughly half of these fish have the earbone deformity, and thus have compromised hearing,” Ms Reimer says.

“Producing farmed animals with deformities contravenes two of the Five Freedoms that form the basis of legislation to ensure the welfare of farmed animals in many countries.”

Deformed earbones could also explain why many fish conservation programs don’t perform as expected. Every year, billions of captive-bred juvenile salmon are released into rivers worldwide to boost wild populations, but their survival is 10-20 times lower than that of wild salmon. Hearing loss may prevent fish from detecting predators, and restrict their ability to navigate back to their home stream to breed.

Study co-author Professor Steve Swearer, from the University of Melbourne, said that the poor performance of restocked fish has been a long-standing mystery.

“We think that compromised hearing could be part of the problem. All native fish re-stocking programs should now assess if their fish have deformed earbones and what effect this has on their survival rates.

“If we don’t change the way fish are produced for release, we may just be throwing money and resources into the sea.”

Banner Image: zalgon/flickr