Education

An alternative to ATAR

A new report offers a glimpse into the next generation of school and university credentials and aims to redefine success for school leavers and graduates

Published 29 June 2020

There is an awkward tension in how Australian schools and universities credential the learning of their graduates.

On the one hand, Australian credentials issued by schools and tertiary institutions are easy to understand, widely used, based on high standards and carefully regulated.

They are relied on for selection and recruitment purposes. They include secondary education certificates awarded to school leavers, the ATAR score awarded to tertiary aspirants, along with a myriad of degrees, diplomas and certificates issued to graduates of tertiary institutions.

However, these credentials are typically silent about a type of learning that is highly valued by students and teachers – and fundamental to future success in jobs and in life. Nor do they say much about what employers, recruiters and selectors say they are looking for.

Our team, at the Assessment Research Centre, has been working with partner institutions to design a new generation of credentials.

Education

An alternative to ATAR

The challenge of changing how learning success is defined, as well as how institutions assess and credential success, was laid out in the 2019 report Beyond ATAR.

The ‘new credentials’ that have now emerged aim to provide a fuller picture of student capability and represent the breadth of what students know and can do, and who they have become, as a result of their learning.

And there are already several examples of these ‘new credentials’ proving themselves in the real world.

Big Picture Education Australia, for instance, is a non-profit company that has a network of secondary schools in the final stages of issuing a new credential to graduates.

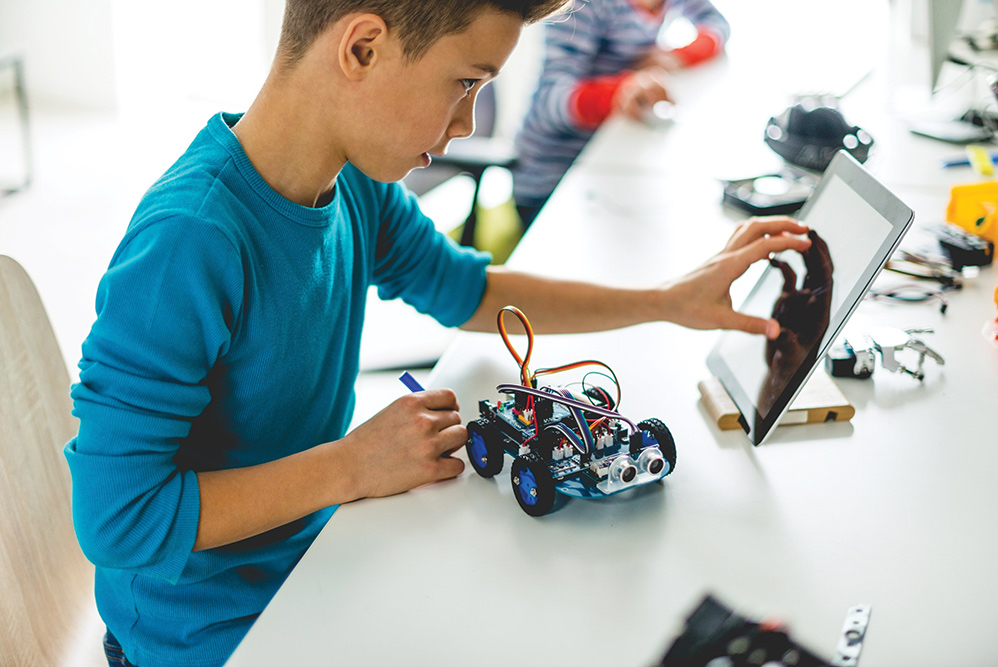

Learning in these schools is personalised around each student’s passions and interests, linking to five mandated learning goals. These include capabilities like knowing how to learn, quantitative and social reasoning, which are complex competencies learned in school and the community.

The design is now accepted and trusted as an alternative to the Higher School Certificate (HSC) by students, parents, and 15 universities, alongside a range of training providers and employers.

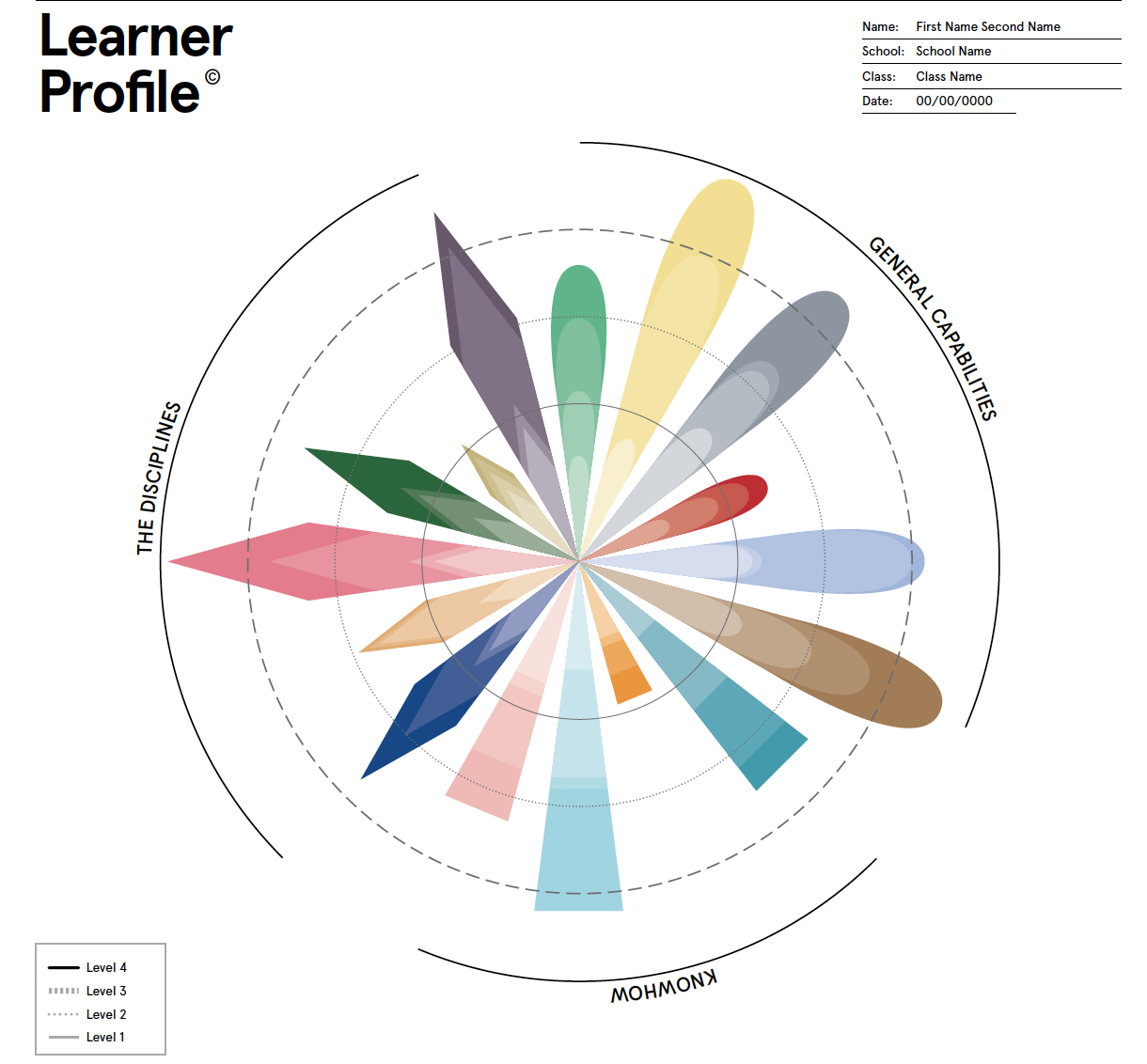

A number of innovative primary and secondary schools working with the University of Melbourne’s Network of Schools have been hard at work developing assessments and micro-credentials that measure complex and general learning capabilities, including critical and creative thinking, communications, entrepreneurialism and so on.

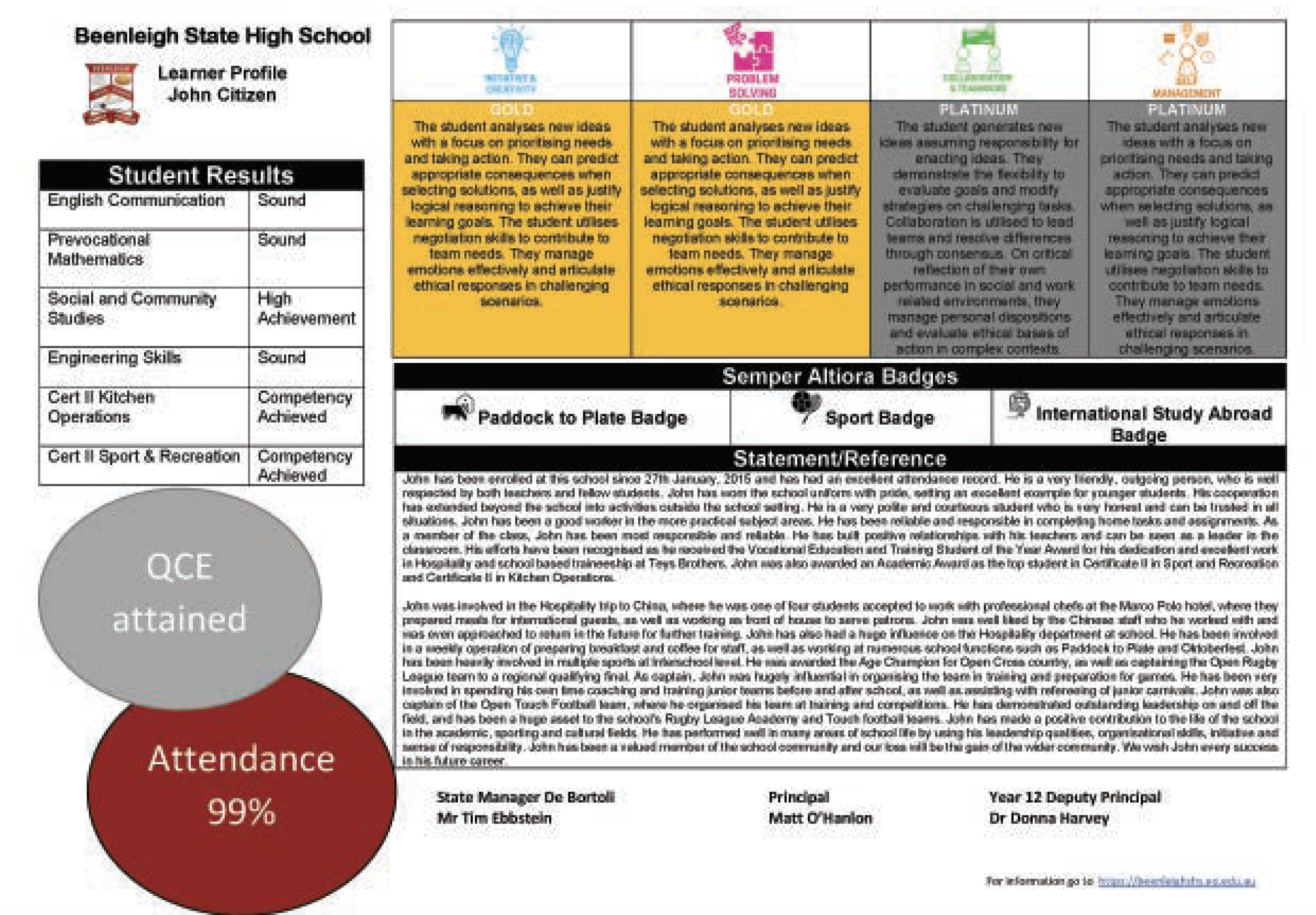

Beenleigh State High School in Queensland is one of these schools. It now issues a comprehensive learner profile that includes micro-credentials (badges) in general capabilities, endorsed by local employers.

At Liverpool Boys High School in New South Wales, Year 12 students will this year be issued with two credentials: an HSC and a credential-based profile using the CAPRI general capabilities framework; the University of Western Sydney has already agreed that the CAPRI report will be treated as equivalent to the HSC.

As different as these institutions are, they have much in common.

Education

Education in extreme times

They have all shown that it is possible to design and build new credentials that are trusted, easy to understand, are standards based, can be widely used and relied on, and provide a broad representation of students.

They are all building on the belief that this new form of credential is fair for all, more accurate and provides better representations of the capabilities of all students, including disadvantaged students who have been typically excluded from the old-style credential.

They all accept the challenge of highlighting the capability of students in a particular type of learning – transferable general capabilities– which have been variously described as 21st century skills, graduate attributes, employability skills, learning skills or enterprise skills.

This consensus is not surprising.

General capabilities have long been recognised as fundamental to a good curriculum. The surprising thing is that learning outcomes as important as these are not already represented in standard credentials.

These first-mover institutions also share a view that success in developing these kinds of attributes and then credentialing them is as important to learners, employers, recruiters and selectors as any capacity to master subject content.

Significantly, they do not see subject mastery as an alternative or in competition.

Education

The world is a classroom

Developing expertise and real depth in mastery of a domain, subject or discipline goes hand-in-hand with developing general, transferable learning capabilities.

You simply do not get excellence in one without excellence in the other.

There is no quick fix for an institution contemplating the development of new credentials. The effort has to go a lot deeper than just issuing new bits of paper, and can take years.

Students have to be given opportunities to learn and demonstrate their capabilities. They need opportunities to think for themselves, develop critical facilities and test claims and evidence outside their own sphere of experience.

Learners need free reign to communicate, and collaborate with others to build knowledge, solve problems or generate creative solutions to complex issues that might not have been tackled before.

They need the opportunity to direct their own learning, free of directive teaching. Their passions and interests, and capacity for perseverance must be allowed to flower.

They must also have the opportunity to express social and community values and ethics in both thought and deed – taking responsibility for their own work to produce, create, build, and contribute to the wellbeing of the community

Our team has developed an eight-step process that aims to create new credentials in which the degree of attainment of students in the general capabilities is accurately represented, and trustworthy.

The process begins by deciding what learning outcomes a credential should cover, then works through stages of credential design, assessment design, moderation, standards setting, quality control and review.

The aim is to embed scalable, reliable, trusted performance-based, developmental assessment and credentialing into programs.

There is much still much to do if this work is to be scaled and spread to other institutions, so all learners can benefit. Much that needs to be done is in the hands of credentialing and assessment authorities.

The apparatus for assessment and credentialing in Australia has not yet caught up with the ‘new credentials’. Still missing are core aspects of any system which support high-quality assessment. These include standards frameworks adaptable to particular contexts, and systems for ensuring integrity, moderation and comparability of assessments.

Australia clearly needs a shift in assessment, credential policy and practice so that our credentials are trusted to attest to what a young person actually knows and can do, and who they are.

Only then will our credentials better give learners what they need to thrive in our modern society.

Banner: Getty Images