Sciences & Technology

Global warming could accelerate towards 1.5℃ if the Pacific Ocean gets cranky

As global surface temperatures rise, new research looks at the potential impact on Australia and its Great Barrier Reef

Published 16 May 2017

The danger of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef experiencing another catastrophic heatwave similar to the recent shocking event is twice as likely if global average surface temperatures hit 1.5°C above pre-industrial conditions.

But it gets worse – the higher the temperature increase, the more severe the threat.

If we hit up to 2°C more than the pre-industrial world, then it almost triples the odds of another marine heatwave on par with the recent event that triggered mass coral bleaching.

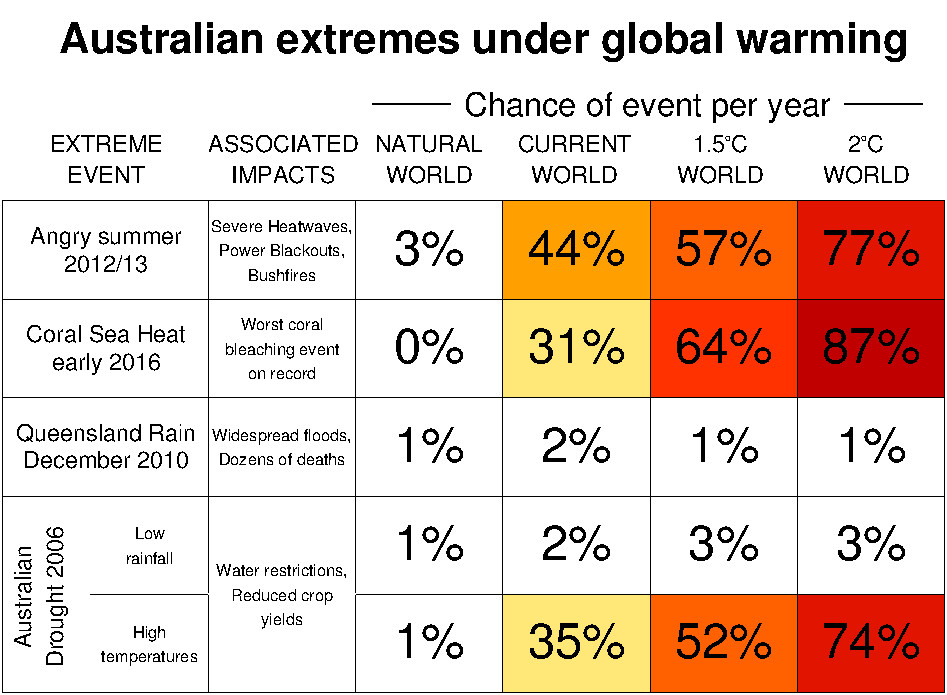

This is just one of the findings from our research for the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate System Science looking at how Australian extremes in heat, drought, precipitation and ocean warming will change in a warmer world.

We’ve already experienced about 1°C of global warming above a natural climate, resulting in more extreme weather events. Some of these events can be directly linked to climate change, for others the link is less clear. But this has meant more heatwaves and droughts – and a coral bleaching event on the Great Barrier Reef last year that has damaged much of the world’s largest coral reef.

So, how will these extremes change in future? If we experience more global warming do these extremes become more frequent?

These are the questions we’ve investigated in our study, published in Nature Climate Change.

Sciences & Technology

Global warming could accelerate towards 1.5℃ if the Pacific Ocean gets cranky

The Paris Agreement of 2015 committed to: “Holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, recognising that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change.”

It is vital we understand the differences in how climate extremes in Australia might change if we limit global warming to either 1.5°C or 2°C.

In our study we used state-of-the-art climate model simulations to examine the changing likelihood of different climate extremes under four different scenarios - a natural world without any human influences, the world of today, a 1.5°C world, and a 2°C world.

As part of our research, we looked hot Australian summers, like the “Angry Summer” of 2012/2013 which saw record-breaking high temperatures across the country.

We already know that human influences on the climate increase the chance of seeing hot summers like the Angry Summer. Our results show this trend continues into the future and with summers like these becoming more and more common. Historically hot summers like the Angry Summer would be cooler than normal if we reach 2°C global warming.

Australia’s summer temperatures are strongly related to the El Niño-Southern Oscillation with hot summers more likely to occur during El Niño events and cooler summers in La Niña seasons. In the past a summer as hot as the Angry Summer would have been very unlikely in a La Niña, but at 1.5°C or 2°C global warming we could expect Angry Summers to occur in either El Niño or La Niña periods.

And this brings us to the Great Barrier Reef.

The sea surface temperatures associated with bleaching of much of the Great Barrier Reef in early 2016 would have been virtually impossible without climate change. If the world continues to warm to either the 1.5°C or 2°C levels then very warm seas like we saw early last year would become the norm. In fact, with 2°C global warming, the sea temperatures we observed around the Great Barrier Reef last year would actually be cooler than average.

It’s a grim warning about what would happen to the Great Barrier Reef if we fail to act on the Paris Agreement. Sea temperatures of the scale and frequency we have seen do not bode well for the future of one of our greatest natural wonders.

In December 2010 Queensland was devastated by severe flooding following very heavy rainfall. Our analysis suggests that this kind of event is an unusual one, but there isn’t much signal for an increase or decrease in those chances. Natural climate variability appears to play a greater role for Australian heavy rainfall events than climate change, at least below 2°C.

Meanwhile, the Millennium Drought across Southeast Australia led to water shortages and crop failure for almost 14 years. Drought is primarily driven by a lack of rainfall but warmer temperatures can exacerbate drought impacts by increasing evaporation. And we found that climate change is increasing the likelihood of hot and dry years like we saw in 2006 across southeast Australia.

In our 1.5°C and 2°C modelling of global warming, these events would likely be more frequent than they are in today’s world.

It is clear that Australia is going to suffer from more frequent and more intense climate extremes as the world warms to, and very likely through, the levels stipulated by the Paris Agreement.

If we fail to meet these targets the warming will continue and the extremes we experience in Australia are going to be even worse.

If global warming causes a rise of 1.5°C or 2°C, we will see more extremely hot summers across Australia, more frequent drought conditions and more frequent heat leading to bleaching of the Great Barrier Reef.

The more warming we experience the worse the impacts will be.

The solution: To limit global warming we need to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions. And fast.

Banner image: The coral bleaching at Lizard Island March 2016/XL Catlin Seaview Survey

A version of this article also appears on The Conversation.