How a numbers man and a botanist are helping business go green

An unlikely research duo have found a new way to channel the carbon accumulation of trees into financial reports, with implications for urban planners and corporations alike

Published 24 September 2015

In Melbourne’s Royal Botanic Gardens – among the majestic lemon-scented gums, newly planted ferns, rustling groves of bamboo and sweeping lawns – a quiet, constant process is unfolding.

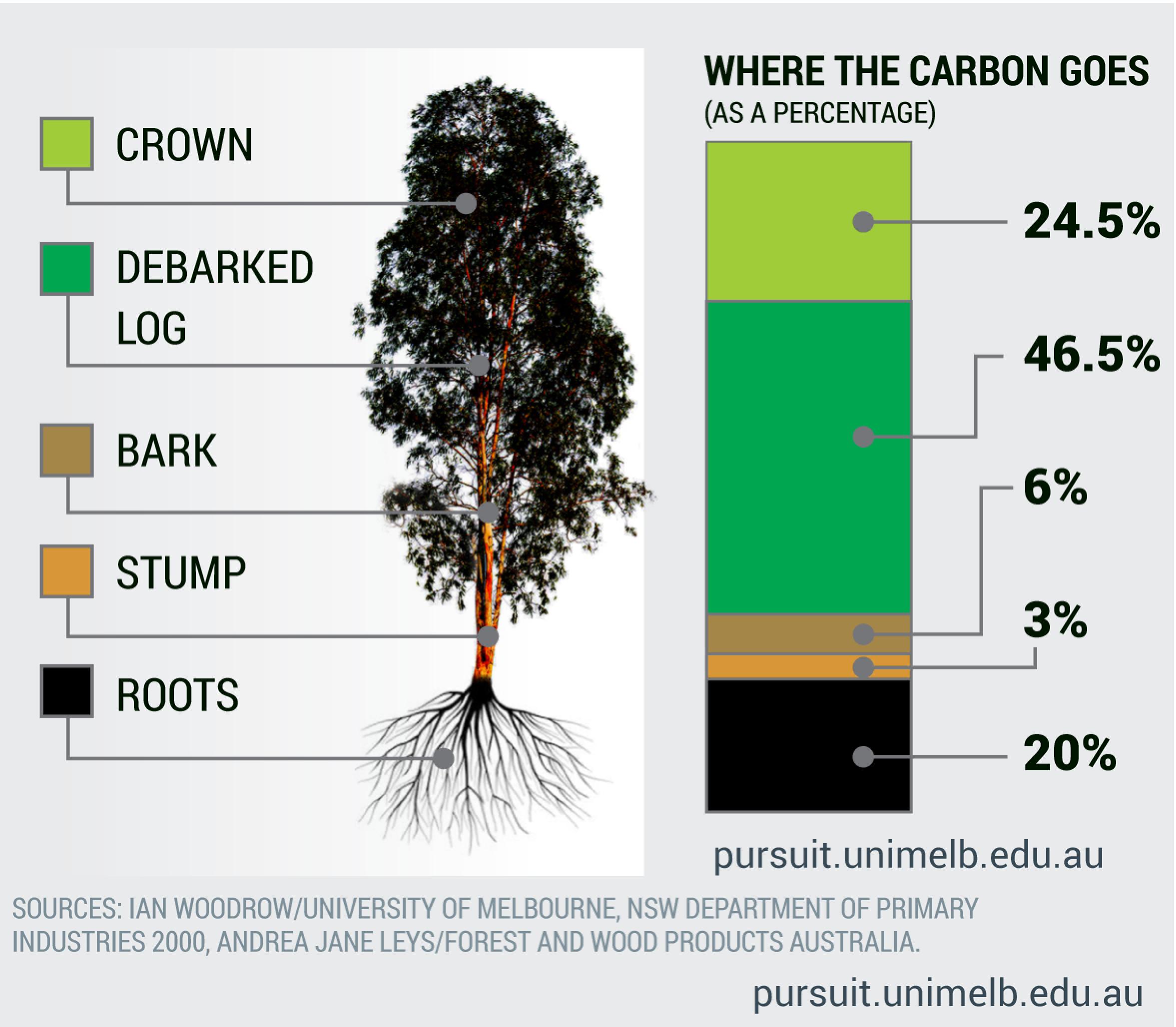

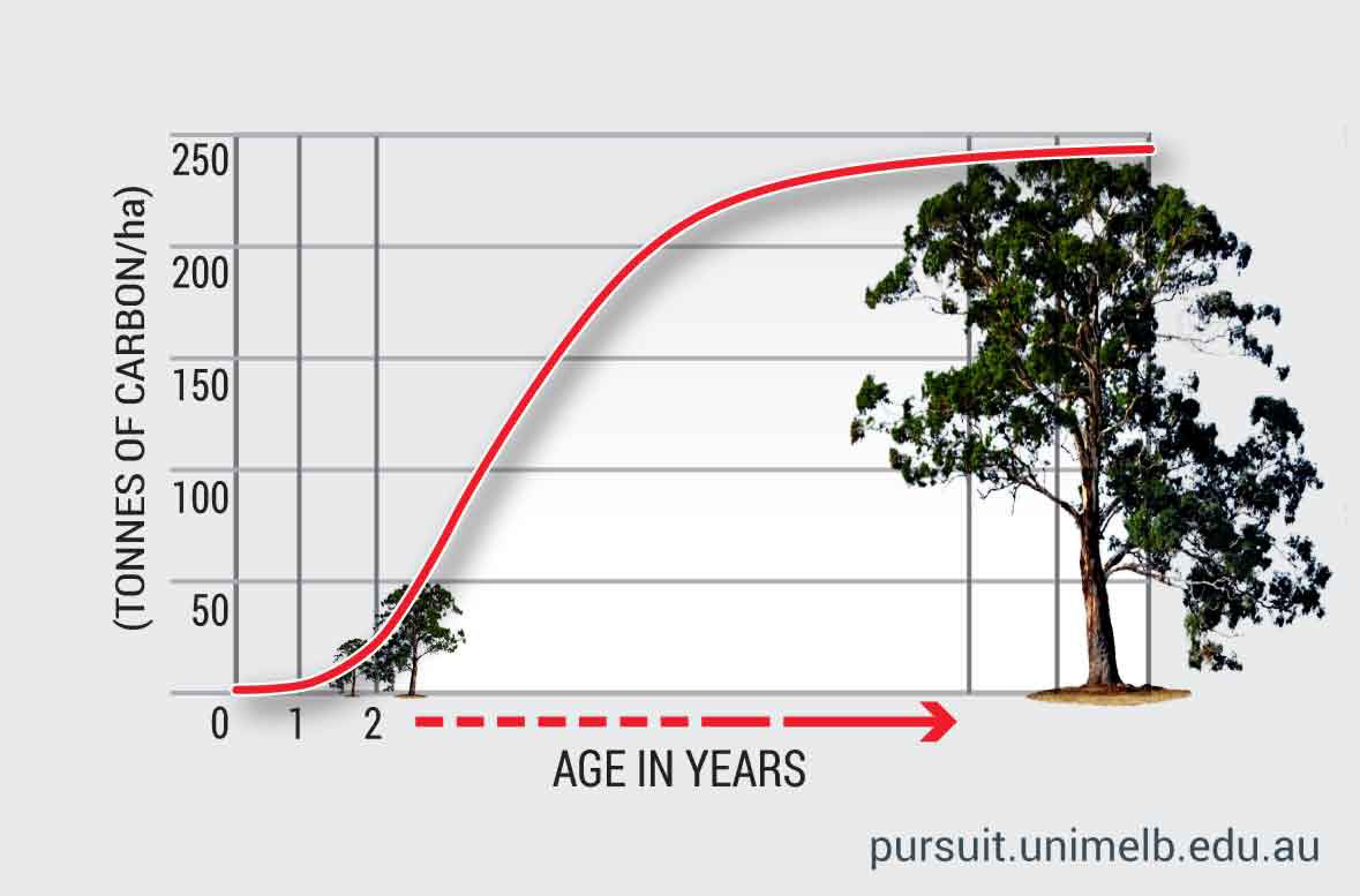

All these plants are growing: taking molecules of carbon dioxide out of the air and water from the soil and joining them together, using the energy from the sun, to build their plant tissues. While a tree is growing, it is “locking” carbon, taking greenhouse gases from the oversupply that’s currently in our atmosphere and storing them in their trunks, stems, roots and leaves.

While visitors enjoy the plants, wander through Fern Gully, dodge bat droppings or take in an outdoor Shakespeare performance, few realise they’re moving through a living laboratory.

The 5700-odd trees have been mapped using high-resolution GPS. Their size and health are known and monitored. There’s been a weather station at the gardens for decades taking weather and climate data, and dendrometers that measure tree trunk expansion in real time have just been installed. This growth is an indicator of carbon being taken out of the atmosphere.

And it’s all happening under the watchful eyes of an unlikely pair of University of Melbourne researchers: Brad Potter, an Associate Professor in accounting from the Faculty of Business and Economics, and Professor Ian Woodrow, from the Science Faculty’s School of BioSciences.

I meet the two at the University’s Parkville campus. As stereotypes might dictate, I’m expecting a suit-wearing number cruncher and a khaki-clad tree hugger with little in common. What I find is two friendly colleagues, fascinated by each other’s work, bringing their vastly different backgrounds together to solve a modern problem: subjecting the complex carbon flows created by urban biodiversity to the ordered requirements of financial reporting.

“I’m a financial accountant,” explains Associate Professor Potter. “My training is in examining the disclosures that organisations make around financial measures of performance and position, but more recently my work has morphed into examining the environmental and social performance reporting.”

His work has implications for investors, boards, shareholders, lenders and even employees – people who like hard numbers and reliable information. But turning trees and carbon sinks into dollar values is difficult. Trees are hard to pin down: there are so many types, with different growth rates in different environments.

That’s where Professor Woodrow comes in. He brings a biologist’s understanding of things like the way turf systems grow and store carbon, or the differences in growth rates between magnolias, lemon-scented gum trees and sequoias.

“Biologists and economists have a lot more in common than we actually think. Plants are intrinsically like an economy,” says Professor Woodrow.

“Plants allocate resources to optimise their outputs.’’

He was surprised to find botanists measure the growth of plants the same way economists measure growth in an economy.

“We use exactly the same unit. We call it ‘relative growth rate’ and an economic measure is also ‘relative growth rate’. It’s denominated in percentage terms, and we do exactly the same.”

A cheeky smile appears on Professor Woodrow’s face as his colleague listens in.

“The fastest-growing plants, of course, are better than the fastest-growing economies, though,” he says with a laugh. “We can have plants with a 50 per cent growth rate, but you think China is great with 7 to 8 per cent growth.”

The academics are one year into an Australian Research Council Linkage Project that will develop a process-based model of the carbon cycle of the Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria, a complex urban ecosystem. The project will test this model in Sydney’s Royal Botanic Gardens and explore alternative ways carbon emission information for urban ecosystems can be reported.

The project had its roots in business practicums as part of the masters course that saw Associate Professor Potter’s students placed with industry partners to complete a consulting task, applying their knowledge to a real-world exercise. One of the first pilot projects was with Professor David Cantrill, Chief Botanist at the Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria, which also hosts the Australian Research Centre for Urban Ecology.

“The students thought they would be looking at business practices,” says Professor Cantrill.

“At the time, it looked like we might need to include carbon accounting in our books in the future. This was the trend for other organisations, but we have a unique situation. We’re not in offices, with carbon emissions limited to things like energy use and transport.

“It’s harder for us to carbon account. So we asked them to take on carbon accounting for the whole garden’s operations.”

The students’ work quickly grew into the Linkage Project. It now has three masters students working on it.

“Where Ian and I struck a chord, within five minutes of trying to get our heads around this, was realising that the scientists have it in their DNA to be able to measure some of this stuff, but the reporting isn’t something they’re as comfortable with. Whereas the reporting is more comfortable for us, but we don’t do science,” explains Associate Professor Potter.

“Ian’s group will do the science, and they’ve got some really cool expensive toys to do that too,” he adds, referring to the newly installed dendrometers.

He also acknowledges the contribution of two other senior academics, University of Melbourne colleague Professor Naomi Soderstrom and Professor Paul Coram, of the University of Adelaide.

The project will fill a significant knowledge gap: the southern hemisphere data on urban trees, including Australia’s, is lacking. Much of the research into tree carbon comes out of America. Australia’s research to date has focused on plantations.

This worries Professor Woodrow.

“You could pull numbers out of the air on Melbourne’s trees but it would be drawing on data from elsewhere or data that’s roughly estimated; it’s not well substantiated by actual measurement.”

This study will be one of the world’s largest measurements of urban tree growth. He expects it will be a globally significant piece of research, partly because the gardens had the foresight to document their plants’ sizes, location and health 20 years ago, providing a baseline for comparison.

The beauty of using the Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria as a test case is that it covers a huge sweep of urban landscape types and plant species in a variety of settings, giving the results relevance for urban planning.

The gardens has an amazing diversity, of course, and that’s a huge strength because within that diversity is just about every urban tree that’s planted elsewhere.

“So, for example, you can predict that the pine tree you plant in (suburban) Brunswick will grow at a certain rate and lock a certain amount of carbon. And you can say that with great certainty,” says Professor Woodrow.

“What’s really interesting about the gardens is that we haven’t yet found a tree that isn’t growing.” This is somewhat surprising for a garden that was established more than 160 years ago.

Over time, the team will learn if the gardens offer a steady “pool” of carbon, a sink that continues to absorb carbon or possibly a net source of greenhouse emissions.

This has important implications for decision-making for other botanic gardens in the short term, and ultimately the urban trees and vegetation planted by local governments, particularly as some councils and governments are committed to being carbon neutral by 2020. Their urban forest strategies will be part of their efforts.

“I’d like them to adopt the model for all their parklands,” says Professor Cantrill.

“They need to understand their ‘carbon cash flow’; understand how their carbon balance sheet is working. Generally, they have no idea because they’ve never needed to.”

These tools will also be invaluable in the corporate world, which is why Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand is an industry partner for the project.

“Our members aren’t just in practice; they work in or provide advice to all aspects of the business sector, including planning and the built environment,” says the body’s Karen McWilliams.

If tools and information become available that help people make better decisions about which trees they can plant that will have a greater net carbon benefit, people will want to know about it. It will make a difference.

“We’re the industry partners who will provide feedback to the researchers, giving them the industry perspective.”

Ms McWilliams says it has been more difficult for organisations to report their environmental performance as credibly as the financial information because the underlying data hasn’t always been as reliable.

“But we are seeing a shift towards more measured and integrated reporting. Progressive organisations genuinely want to be better able to measure their carbon reduction activities. This project will help with that aspect of reporting, particularly on commitments to go carbon neutral.”

All of which is music to Wayne Wescott, Chief Executive of Greenfleet, a non-profit organisation that plants native forests to offset greenhouse gas emissions. “We have strong data for our broad-scale planting, but we recognise that urban greenery – with which we’re increasingly involved – has a different set of data points. We need defensible numbers and are happy to see this being developed.”

I ask Professor Woodrow and Associate Professor Potter what comes next. For example, could the model they are developing be adapted to measure water costs and flows in urban forests? Professor Woodrow’s eyes light up.

“It’s funny you should say that because the company that supplied the high-tech dendrometers got really excited about the project and they’ve offered to come down and install sap-flow meters, which is great.”

His colleague interjects. “See? Another cool toy, right?”

Banner image: The greatest gold glimmering through the trees by @sage_solar, via Flickr