Health & Medicine

False labelling hides the truth about superfoods

Our responses to food are more unconscious than you might think, but new technology can really tell what you like and dislike

Published 4 July 2017

A generation of cooking-based reality TV shows means your guests at a dinner party will probably be able to talk about the way a flavour changes as they chew, or apply the new vernacular to describe the “mouthfeel” of your dish.

Whatever they really think, they’ll probably been nice enough to compliment the chef. But for food manufacturers and other industry professionals, someone’s true reaction to a food is far more valuable.

In the years since British and Italian scientists first proved they could convince a test subject that a potato crisp was more or less fresh by simply changing the sound they heard while eating it (picking up a satirical Ig Nobel prize for nutrition along the way), food manufacturers have developed a sophisticated understanding of the factors behind our enjoyment of food. These factors include its colour, shape and sound; as well as the presentation on the plate, or its packaging.

But to fully test a food product before launching into a new market requires a new set of tools.

“One thing we are trying to tap into in our research is the emotional responses of the consumer – or their biometrics,” says Dr Sigfredo Fuentes, who runs the University of Melbourne’s new sensory lab.

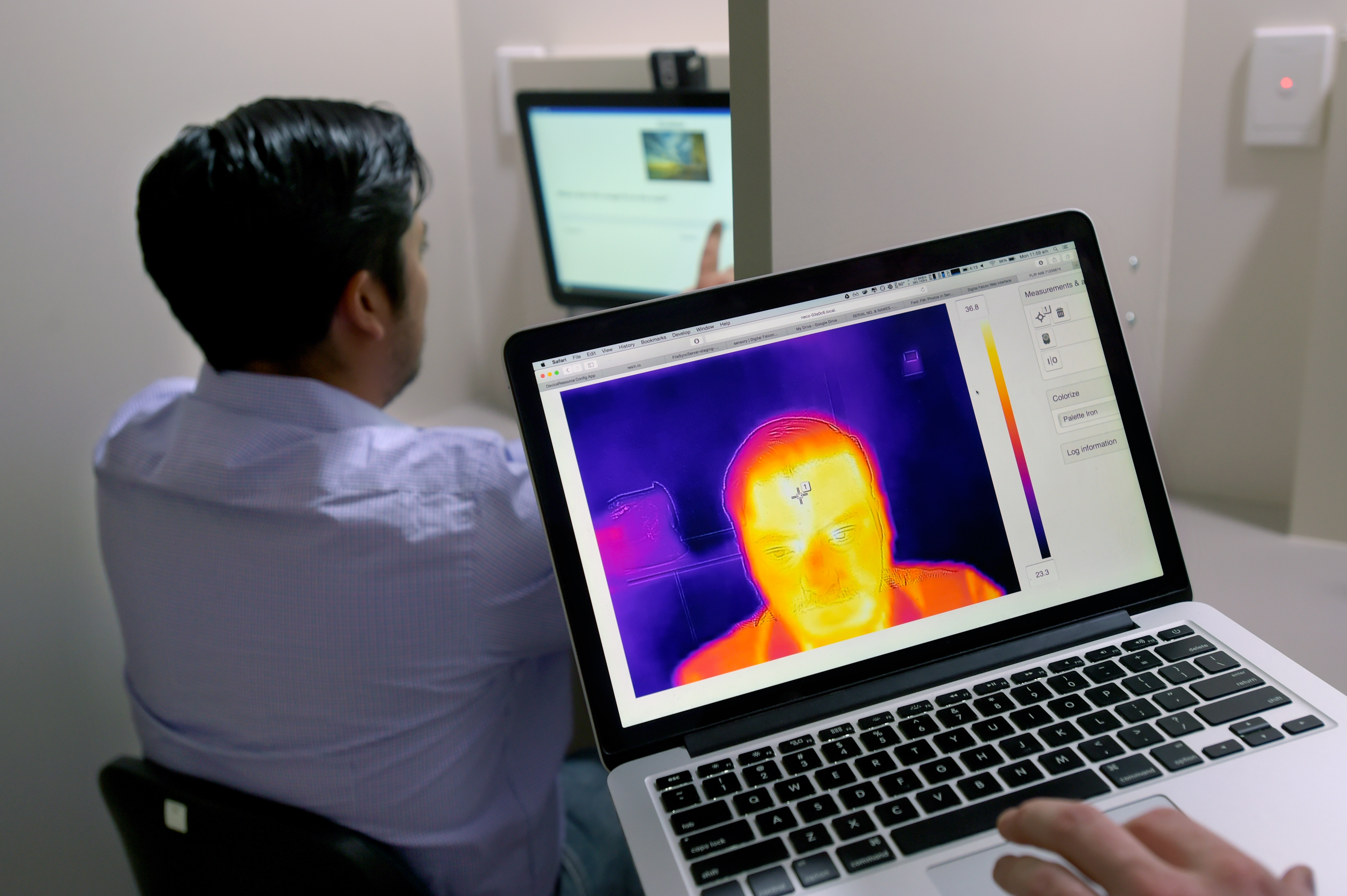

Dr Fuentes and his team combine traditional testing – asking people what they like about a food – with biometric data gathering. As subjects eat, their body temperature, heart rate and facial emotional responses are all tracked as indicators of their unconscious responses, starting from when the food is first revealed to when it is swallowed. Eye tracking also shows researchers what part of the food or packaging is capturing the attention of participants.

Health & Medicine

False labelling hides the truth about superfoods

As a wine scientist, Dr Fuentes knows the effect and value of subtle changes to the aroma, texture and colour of food and beverages.

“The conscious part of our response to food is around 20 per cent, and that’s what people are able to tell you about when they take part in a sensory analysis,” he says.

“But according to the latest research, 70 to 80 per cent of the response is unconscious. The biometrics allow us to tap into this ‘real’ response from people.”

In the sensory lab, participants sit in isolated sensory booths and are passed food and drinks through a door, directly from the lab’s commercial-grade kitchen. The researchers can adjust the lab to simulate different environments by changing the colour of the lighting. Participants receive instructions and stimuli from a touchscreen; this is also where they give their conscious response to the food and drinks.

The entire experience is also captured by a video and infrared thermal camera in each booth, and analysed using a facial recognition programs that can measure even slight changes in expression, offering important clues that are then interpreted by Artificial Intelligence (AI) algorithms about how the subject is responding to the food.

Dr Fuentes’ colleague Damir Torrico imitates how many us react to a sour lemon flavour by pursing his lips and frowning. “The programs actually measures that reaction when you see and taste the product,” he says.

“These unconscious reactions are more reflective of the true feelings you have for the product in the moment. Then there is a thinking process and maybe a couple of seconds later, you might rate the product according to what you like. But that also involves some familiarity, some other background information that is interfering with the response,” says Dr Torrico.

This is especially important for Western brands trying to break into new markets in Asia, where tastes and even reactions to the packaging of food can be radically different.

Dr Fuentes gives the example of chocolate in China. While chocolate has now become accepted as a luxury food, the initial approach of most confectionary companies rarely resonated with Chinese consumers. For example, Cadbury expected Chinese consumers – who had no experience with chocolate and little experience with sweet flavours – to behave like Western consumers and buy chocolate by the block or large bar. But they did not have the appetite for large servings of such a sweet and unfamiliar luxury.

But Ferrero Rocher, with its individual foil-wrapped treats, proved to be better-suited to the Chinese market where it was seen as an exotic foreign gift for an important associate or sweetheart. In this way the Italian chocolatier found its place in the high-end Chinese market.

Packaging also plays an important role in the success of products. Dr Torrico says having consumers from target markets compare new products to familiar ones, and then categorise them by expectation and experience – a process called Qualitative Multivariate Analysis (QMA) – allows companies to avoid a product flop. He says this is especially true for small and medium enterprises, which do not have the resources for large-scale research and development.

“If you are a food company trying to introduce something to China that you have had success with in Western countries, you will probably run into problems – there are a lot of differences in the culture around food,” Dr Torrico says.

“It’s going to be a problem for all food companies until they understand it’s a different market, with different consumer perceptions, different cultural habits and ways of consumption.”

Small and medium Australian brands can rarely afford to make mistakes when entering a new market. Hollis Ashman, the Enterprise Director (Research & Development) at the University of Melbourne’s Unlocking the Food Value Chain research hub, says companies hoping to export to Asia need to be aware of the cultural biases of both consumers and their own staff.

“We aren’t aware of our biases until we talk to other people, and this can catch a brand off-guard,” she says.

Sensory analysis is essential, as is formulating a product that balances novelty with familiarity. Ms Ashman points to Cadbury’s launch of Vegemite-flavoured chocolate as a successful example: the product’s flavour had strong hints of salted caramel, allowing customers to indulge their curiosity without straying too far from familiar tastes.

There must also be an obvious space for the product – and its packaging – in the new marketplace. Biases will always be a challenge for a new product, but they can be measured, and bypassed, with thorough planning, says Ms Ashman.

“The successful export companies are generally the ones that do thorough research before they launch – of the food science and technologies they can implement, of the local competition, of supply chains, and most of all, of the people they hope will buy their products,” Ms Ashman says.

Dr Fuentes emphasises that even when companies apply rigorous surveying, they should still consider biometric testing to reduce the risks of marketing products in markets with different cultural biases around food.

“The information you get from traditional product testing is further reduced in Asian countries, mainly because they try to be polite,” Dr Fuentes says.

“If you really want to know what the reaction to a product will be in China, you need to have the real response. That’s why the biometrics are important – the biometrics combined with AI will tell you things that people can’t or won’t.”

Banner image: publicdomainpictures.net