Arts & Culture

Lucky discoveries of lost ancient history

The myth of Narcissus as told by the Roman poet Ovid isn’t so much about narcissism and self-discovery, as about what it is to transgress the norms of male sexuality

Published 6 September 2019

Was Narcissus really a narcissist?

The Greek myth about the beautiful Narcissus, who was too proud to love any of his admirers and was condemned by the gods to fall in love with his own reflection, has always been seen as a warning against excessive self-love.

But is this really the best way to read the story?

Retold at the beginning of the first century CE by the Ancient Roman poet Ovid in his Metamorphoses, the story has much to say on a subject that is still uncomfortably resonant today: toxic masculinity.

The Narcissus tale in Book III of the Metamorphoses, in its barest outline, is actually a story about a teenage boy who rejects the sexual advances of some other teenagers, and then starves to death staring into a duck pond.

Arts & Culture

Lucky discoveries of lost ancient history

His downfall is framed as cosmically just, but the judgement can be read as not one against self-love, but as a reflection of the aggressive way society punishes any manifestation of teenage male sexuality that contradicts the norm – the idea that to be a man is to be perpetually on the look out for sex.

In reading the Narcissus tale today, the biggest difficulty a modern audience faces is to somehow divest our protagonist of all of his cumbersome cultural baggage.

Just as any knowledge of Freudian psychoanalysis fundamentally ruins the experience of trying to read Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, so the mental equation that Narcissus, the mythological boy = narcissism, the peak of egotism, obscures what the tale is actually telling us.

This equation turns the reader’s gaze inward and prevents us from seeing the interesting monsters in our peripheral vision, in this case the toxic norms of male sexuality.

The most important thing to remember when reading the story, then, is that Narcissus’ “arrogance” isn’t arrogance in quite the way we imagine – that is, excessive self-love.

Indeed, the sole evidence Ovid gives us of Narcissus’ “hard arrogance” is that, despite being enthusiastically propositioned by everyone he meets, “no young men, no girls touched him”.

Health & Medicine

How challenging masculine stereotypes is good for men

Ovid might call this arrogance, but it sounds more like typical self-isolating teenage angst – Narcissus, in case we forget, is just sixteen years old in the story and clearly not particularly well socialised.

What we actually hear from Narcissus himself bears out this diagnosis.

The narrative justification for his punishment is his rejection of the nymph Echo, whose power of speech has been significantly limited by the goddess Juno – she can only echo or repeat what has already been said.

As Echo ambushes him in the forest, looking like an outtake from a child safety warning about ‘stranger danger’, Narcissus shrieks, “Get your hands off me! May I die before you have power over me!”

This is an unexpected response from someone ostensibly too proud to live.

Narcissus’ reason for rejecting Echo is not, as we might imagine, that she simply doesn’t measure up to his high standards. Instead, Narcissus seems to consider her outstretched hands a threat to his own autonomy, rather than an expression of her desire to subject herself to him.

This attitude, again, seems more revealing of insecurity and emotional isolation than snobbish arrogance. Of course his fears for his own freedom will in the event prove tragically well-founded.

Arts & Culture

Rome’s Augustus and the allure of the strongman

It is also a nuance completely glossed over in both the 1955 and 2004 Penguin Classics translations that instead substitute the more conventionally narcissistic phrasing, “I would die before I would have you touch me!” and “May I die before you enjoy my body,” respectively.

What seems key to the poet, however, is not Narcissus’ emotional state, but its impact on his behaviour, specifically, his sexual behaviour.

After he rejects Echo, another of Narcissus’ spurned would-be lovers raises his hands to the sky and prays to the goddess Nemesis (‘Righteous Vengeance’) that Narcissus be made to feel the rejection that they all feel.

Nemesis, as we all know, obliges.

But at this point we need to take a quick dive into the Ancient Roman context if we are to examine the implications of Narcissus’ unseasonable frigidity.

Roman society expected its young men to begin embracing their education in the ‘Art of Love’ in their mid-teens, around the time they begin wearing the toga virilis – the symbol of manhood.

This was despite the fact that many young men would not marry for the first time until their twenties. Emotional maturity clearly wasn’t a prerequisite for sexual maturity.

In this sense, Roman society isn’t really so far from contemporary Western society and its acceptance of teenage boys’ apparently uncontrollable horniness.

It’s this acceptance or indulgence, which explains the often atrociously lenient handling of sexual assault and rape cases by our legal system, as well as the unwillingness of young men themselves to come forward as victims of sexual assault.

Arts & Culture

The rise of the microgenre

Why then, even at our comparatively progressive point in human social history, have we never re-examined Narcissus’ public image in light of these parallels?

His story, in its own idiosyncratic way, has just as much to tell us about normative gender roles as Helen of Troy’s or Medusa’s.

The answer might, perhaps, be an unconscious resentment that transcends both time and gender.

Contemporary Western society is just as entranced by youth, beauty and fame as the Romans were, and the prospect of a famously beautiful youth who exploits none of these advantages might strike us as simultaneously miserly and wasteful.

Fame and beauty, in our culture, aren’t just enviable assets – there is a transactional relationship implied in their value.

So, while we do love the famous and the beautiful, we also expect them to love us back, to repay the adoration of their fans with suitable gratitude.

The real problem with Narcissus then, both for the Romans and for us, is that he just won’t return our love.

And really, when you think about it, he shouldn’t have to

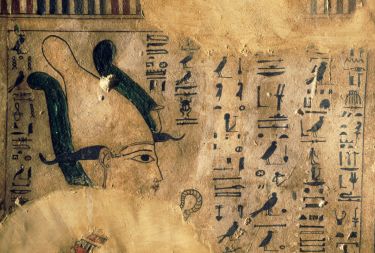

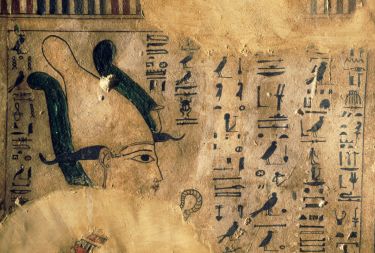

Banner: Narcissus as painted by Caravaggio/Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica/Wikimedia