Education

Instructional teaching explained

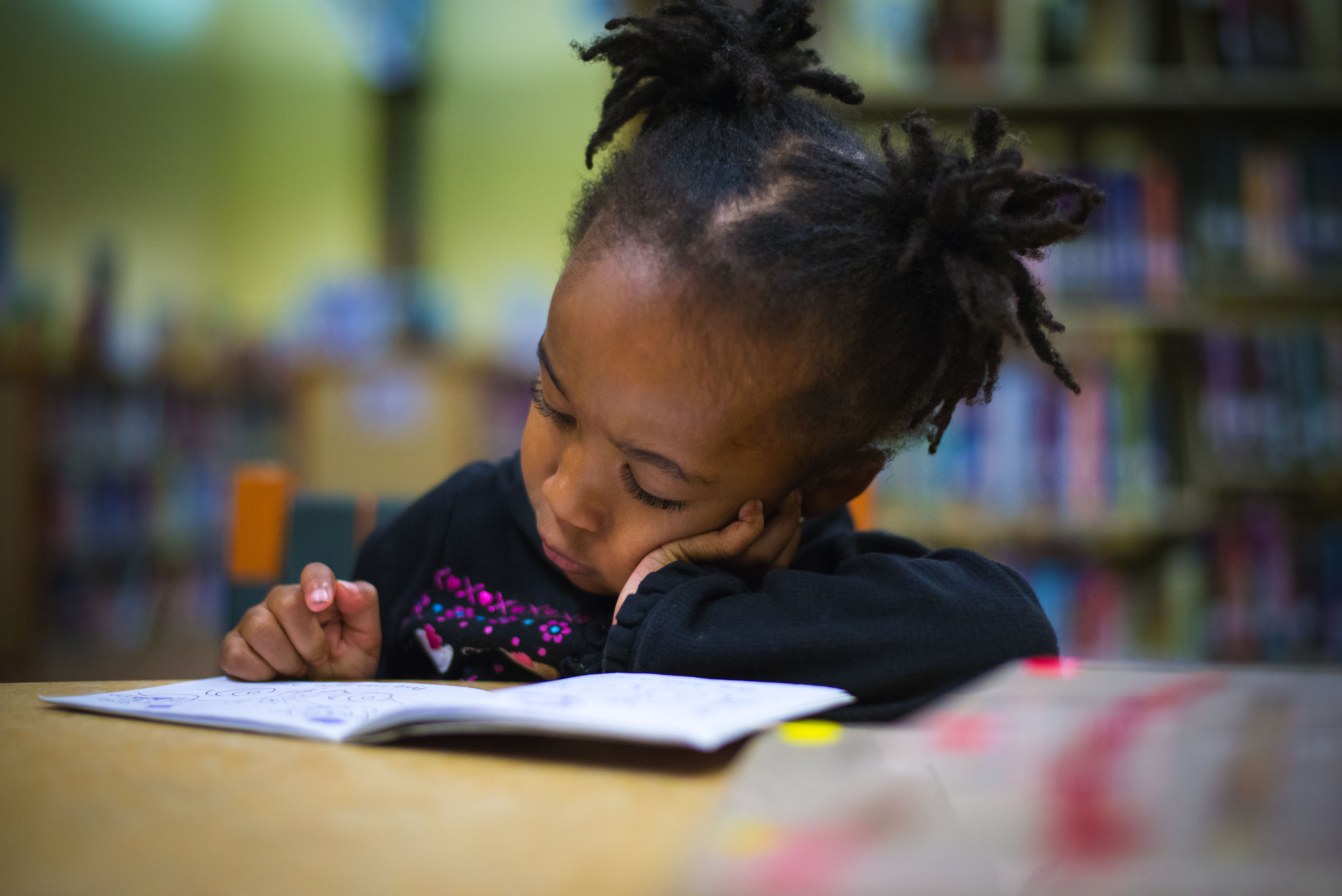

How quality teacher interaction with children pays off in their future education and development

Published 27 March 2017

We know that quality early childhood education is critical, but what is actually happening in kindergartens, childcare and homes across Australia?

Over five years, dozens of researchers from the University of Melbourne and Queensland University of Technology have ventured deep into family homes and early childhood education services, tracking almost 2500 children aged from three to eight in an unprecedented Australian investigation.

Their ambitious mission? To determine the interactions, environments and experiences that give a child the best educational start in life. Or as chief investigator Professor Collette Tayler sums it up, to write the prescription “for the development of a child’s mind”.

They found that across the landscape of childcare and early learning – that’s everything from family day care to pre-school – Australian children generally enjoy high levels of emotional and social support. But only one per cent of them experience high-quality instructional engagement with adults in their play, and this ingredient is fundamental to their cognitive development and future learning.

Further, the children who most need these quality moments – “those who have more risk factors, who are most disadvantaged” – are the least likely to encounter programs capable of delivering them, says Professor Tayler, director of the landmark Effective Early Educational Experiences (E4Kids) study, which has just published its conclusions after almost a decade of work.

Education

Instructional teaching explained

These findings provide powerful insights for parents and educators seeking to advocate for children’s needs, Professor Tayler says. “This is the first time we have formal, empirical evidence of that link to children’s outcomes.”

They also represent a profound challenge to policymakers.

“The rhetoric around early childhood and early intervention and its importance for a child starting well is there in the policy, but the planning for services is largely left to the market.

“The result is that the most disadvantaged children live in areas where the market fails them – it doesn’t provide them with the better quality education and care that they need.

“Governments and authorities need to be a little more directive in closing the gaps,” she says. As the final report observes: “There are few social justice issues more vital than building a better life for all children, and a more prosperous nation.”

Work on the E4Kids study began in 2008 with the recognition that there was a gap in understanding how the quality of early childhood education and care plays out in driving children’s outcomes. So began the mammoth task of designing the investigation and recruiting into it 2500 three-year-olds and their families, carers and teachers from the social and geographic spectrum.

The exercise required intimately exploring the health, home-life and socio-economic circumstances to control for variables. The nature and organisation of the programs each child attended were recorded, and the quality of adult-child interactions observed and assessed. The children’s cognitive abilities were tested over three years, and then all the findings were evaluated against grade three NAPLAN scores.

At the core of the analysis were the observations researchers made of the exchanges between children and the adults teaching and caring for them. Their challenge was to distinguish emotional/social support, as distinct from instructional support.

“I know it sounds like school, but we are not referring to it in that way,” explains Professor Tayler. “What we are talking about is the way an adult talks to a child when they are in a play situation, and what they are drawing out in their thinking and in their language development.”

For example, in an emotional support situation, the adult – be it a childcare worker or a pre-school teacher – might perceive that a child is hesitating to join in play. That adult may go in to help the child connect, or remind them to use their words – such cues reassure and support the child.

“But with instructional support, the educator is probing and pushing the child’s thinking, asking them about something they are doing rather than just saying ‘well done, good boy’ or whatever,” says Professor Tayler. “They have a back and forth conversation – they probe.”

In the context of reading a book, even to a small infant, it involves having a conversation with the child, watching that the child looks at something – ‘you’re looking at the bird’ – and making that connection for the child’s mind.

“It’s quite simple, but not always easy,” Professor Tayler says. “We might think that happens at school, but that is way too late.” It’s this early engagement that underwrites better results in school, as the study tracked.

Such interactions may only take a few more seconds of adult time, but the payoff for the child’s learning is powerful, says Professor Tayler. It isn’t a question of taking the fun out of play. “It’s a matter of just slowing down a little, doing the same things but having clearer in your head that you want to pull out a little more.”

Keeping children clean, fed, watered and safe are accepted minimal requirements of any home, care or educational environment. Professor Tayler argues that the responsibility to support a child’s cognitive development, “to help build their thinking and their minds and their language,” should be similarly imperative.

Education

Making a case for teacher aides

The study found that access to instructional support was extremely low across all settings – childcare and kinder environments - although in the latter it was marginally better. Professor Tayler hopes the E4Kids report helps to break down distinctions between the “care” obligations in childcare versus kinder programs.

She also urges policymakers to recognise the social and economic benefits of investing in professional development for adults who work with children to refine their instructional techniques, and also in outreach to families so that the same strategies are ingrained in daily routines at home.

Such investment should target the geographic and socio-economic gaps identified in the study. There is a strong justification to prioritise investing in programs in the least advantaged neighbourhoods, and to put more focus on programs for toddlers, says Professor Tayler.

“The bright children who have been developed this way at home will do well anyway,” she says.

“But the children who don’t get much of this interaction are the ones who most need it, and who then make great gains from it.”

Banner Image: Cherie Joyful / Flickr