Arts & Culture

To bear witness in dangerous times

A new exhibition highlights the stories and experiences of whistleblowers who have spoken out and suffered for doing so

Published 26 February 2021

“I was hired when I was 22 years old and I saw an ad on Facebook to go on a working holiday trip overseas. I thought that was cool at the time. So, I rang the number listed on the ad and they sent me to Nauru within three days.”

These words, from former migration officer Nicole Judge, who worked at both Manus Island and Nauru offshore immigration detention centres, show how ill-equipped she, and others like her, were for the horrors that they would later witness.

But, when those like Nicole have chosen to speak out about violence and abuse, they are either ignored or shut down.

At a time of ‘fake news’, discredited testimonies and attacks on the credentials of those who do ‘speak out’ about abuse, violence and corruption, the need for people who are willing to speak truth to power is most pressing.

In my research into the ethical degradation of ‘office’ that accompanied a policy of mandatory immigration detention, I examined how those working in toxic settings negotiated their ethical and professional obligations.

Arts & Culture

To bear witness in dangerous times

I traced the ways that the violence of immigration detention impacted not only on those seeking refuge, but on those ‘doing the detaining’.

Some left in despair, others turned to self-harm, some became complicit in the violence and others spoke out.

How staff manage their exposure to violence and misconduct can vary, from collusion, to denial, compliance, and resistance. Although some responded with quiet acts of kindness, others simply departed the institution, with their own health compromised or in an attempt to advocate after leaving.

As long ago as 2011, a Comcare report noted that the institutional environment affects staff as well as those detained, with officers in detention having to undergo exposure to the “deaths of detainees and the stress of having to deal with it” and talking people out of suicide “every single day, all day, every day”. For some, like former detention officer Diane Parker , witnessing such violence led to their own loss of life or to suicidal ideation.

Members staff working in this sector have been expected to demonstrate loyalty to the department as their primary obligation, despite the tension between their professional codes of conduct, their undertakings to their employer and their ethical values.

The toxicity of offshore processing and immigration detention has led to many staff admitting that it has caused changes in their behaviour which they would rather forget.

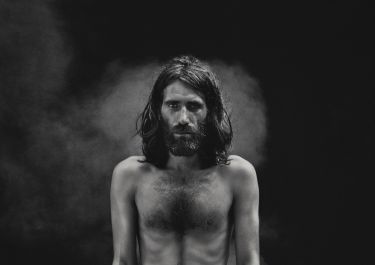

Through research I conducted in collaboration with artist and scholar Hoda Afshar – resulting in a new creative work produced by Afshar, entitled Agonistes– the stories and experiences of whistleblowers in a range of settings, who have spoken out, and suffered for doing so, are examined at close range.

Politics & Society

Academics call for an end to immigration detention

Each of the participants share the barriers that were put in the way of the truth, including being forced to endure personal hardship for speaking out.

But it’s evident that the choice to speak out was clear.

As Nicole Judge reflected:

“I thought I can’t be here and not record what’s happening. I can’t not let the public know what I’m seeing, because I thought it’s so important to bear witness.”

Others, like former Occupational Health and Safety officer Rod St George, similarly stated that he was simply unprepared for the “situation that I was placed in in New Guinea Manus Island” which he described as far worse than any prison he had worked in:

“I ultimately felt that I couldn’t continue working in a situation like that, that was so plainly wrong. It was just ethically abhorrent to me… I often felt as though I was in my own personal prison.”

While sent there to improve health and safety, he was prevented from doing so.

Importantly, those who speak out are not simply ‘disgruntled public servants’ but people with an abiding commitment to truth in the face of startling abuse and misconduct.

They are those who ‘speak from below’.

Politics & Society

How did it come to this?

The abuse and misconduct they sought to uncover was systemic, and it happened because those in power either “allowed it or encouraged it to continue”.

In each instance, those who participated in this project spoke of the conflict between the loyalty to their employer or to their family, and their loyalty to a higher obligation – to ethics.

While disclosure often came with enormous relief, it was typically apparent that nothing changed as a result.

Rod St George expected, for example, that his disclosure would send “shock waves” through the Department, but it did not. Disturbingly, those who could have made a difference, who had “power to make laws and enforce them, simply didn’t”.

Instead, the very laws designed to protect whistleblowers were used to intimidate and stop people from speaking out. Confidentiality laws, gag orders and threats of criminal prosecution, as well as more furtive, insidious obstacles including personal surveillance, discrediting by family members and attacks on their professional and personal lives were used against them.

For disability care worker, Julie Sullivan, while witnessing abuse and corruption in a disability care setting was horrific, so too was the victimisation she was subject to afterwards:

“If you could imagine any whistleblower story you’ve heard, mine is up there because they were relentless… they are the strategies that the bureaucrats use to silence people who expose corruption or abuse or rorting, and it works because they crush you to the point that you become so lonely and powerless and you become an outcast or a self-imposed outcast.”

Politics & Society

Australia’s place at the human rights table

All whistleblowers interviewed faced similar responses: denial and intimidation.

Institutions closed in on themselves, shutting down avenues for exposure, dedicated to one primary value: that of preserving the institution itself.

Those who speak out occupy the liminal space of being within and outside of the legal order, cast either as hero or traitor, who contest the unfairness and illegality evident in society, who witness it and are then expelled from that order as punishment for doing so.

Like the Greek tragedy of Antigone, those speaking out have appealed to a higher ethics but been sacrificed for doing so.

Truth telling is embedded in relations of power that shape, constrict and modulate the capacity of whistleblowers to speak and be heard.

The actions of whistleblowers were motivated by the desire to ensure the truth was known. Often, they were the voices for those whose voice could not be heard or even spoken. As Julie recounted, we are “voice of the voiceless. We are the people who speak for the people who can’t”.

But they often end up as victims themselves.

Agonistes was commissioned by PHOTO 2021 which runs from 18 Feb - 7 March. The University of Melbourne is a proud Education Partner to PHOTO 2021.

Banner: Hoda Afshar, Agonistes (still) 2020, 1-channel digital video, colour, sound. Courtesy of the artist and Milani Gallery.