The spambots are coming for your job, Aldous Huxley

Robotic ‘Spam’ tins recreating dystopian fiction ask us to consider the role of AI, art and animals in society – and how they intersect

Published 12 June 2024

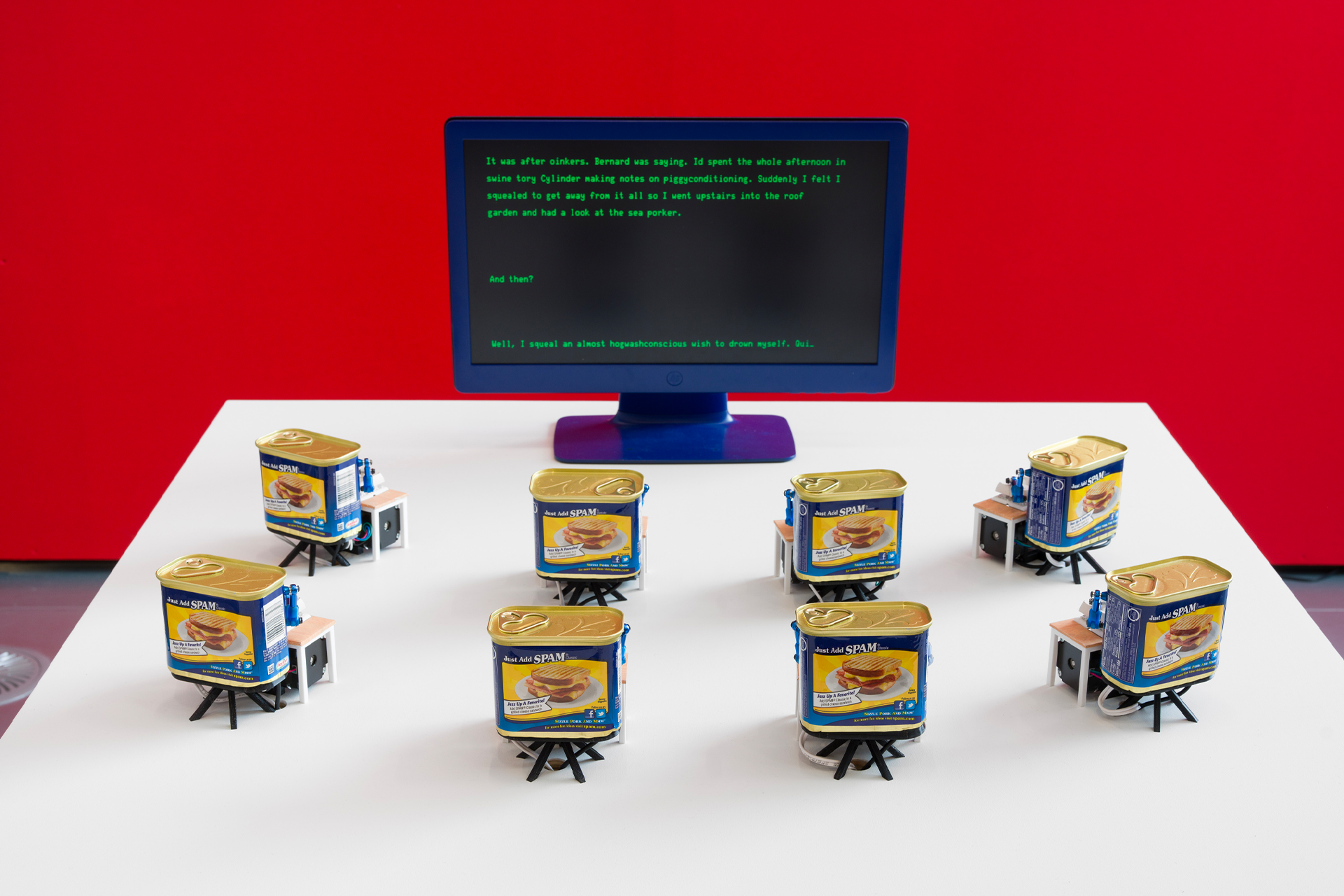

An ensemble of miniature robots is currently toiling away in Science Gallery Melbourne’s NOT NATURAL exhibition.

The exhibition explores the uneasy interface between natural and artificial systems. The miniature robots are called Spambots. With bodies made of Spam cans, they reproduce an AI interpretation of a classic dystopian novel.

Each Spambot has a small keyboard with four letters on it. Together, the Spambots can type the whole alphabet. Their text is generated using a large language model run by a neural network fine-tuned on Aldous Huxley’s novel Brave New World, where random words have been swapped out for words about pigs, bringing a porcine slant to the famous story.

The installation asks questions about both AI and industrial farming. In Huxley’s novel, each character is born into a caste in much the same way industrial farm animals (including animals that become Spam) are born into their fate.

Both Huxley’s characters and pigs in industrial farms are subject to control and manipulation. However, unlike the unfortunate humans in Brave New World, factory-farmed pigs are not fed euphoria-inducing drugs like Soma to ease their stress and suffering.

AI and art

Machine learning is going to touch most people’s lives in more profound ways than just the creation of smarter internet spam. The production of art is no exception.

AI in art is not without controversy – for instance, many image generation models have been trained on copyrighted materials without the artists’ consent.

People are contemplating whether AI art has any merit or might undermine creative jobs. While it will certainly impact how content is created, it also opens up a whole new world of possibilities for artists.

Just as the advent of photography changed painting, AI has the power to change the role of the creator in any artistic process involving technology.

For instance, Sougwen Chung has trained AI systems to be robotic collaborators in the creation of physical artworks. The artist Niceaunties uses generative image and video generation to create a surreal universe inspired by influential women in her family.

Many of Neil Mendoza’s works use smart technology. For instance, the Robotic Voice Activated Word Kicking Machine delves into our interactions with chatbots.

We engage with these devices as if conversing with friends, and often overlook the data trails we leave behind. This installation makes such trails tangible, using projection and robotics to visualize the consequences of our digital interactions.

Most corporate uses of technology like AI are focused purely on extraction of money and attention. It’s up to creatives and thinkers who aren’t bound by corporate constraints to plant the seeds of a sustainable and inclusive future.

Health & Medicine

Overcoming our psychological barriers to embracing AI

Animals and art

Like Spambots, there are other artworks that unsettle our often negative moral views of animals:

Australian artist Patricia Piccinini’s sculptures are often strange hybrids of human and nonhuman forms. Her exhibit in NOT NATURAL is a half orangutan and half human creature who lovingly holds two infants. It invites us to reassess the boundaries we set up between Homo sapiens and other animals.

Neil Mendoza’s Fish Hammer empowers a live goldfish to smash miniature furniture with a hammer, playfully reversing the normal dynamic between humans and marine life. Fish Hammer illustrates the sometimes-destructive impact of human technology on the underwater world.

Some animal-featuring artworks themselves push ethical boundaries. Marco Evaristti’s installation ‘Helena’ comprised a series of food blenders filled with water and live goldfish. Visitors could choose to switch on the blenders, killing the fish. Most visitors refrained, but one or two did so.

In 1975, Australian artist Ivan Durrant dumped the body of a freshly killed cow named Beverley outside the National Gallery of Victoria as a commentary on animal rights and human hypocrisy.

Nonetheless, we might ask whether works that harm animals or their bodies tend to reinforce rather than critique human domination.

AI and nonhumans

In Spambots, we see a confluence of harm, death and technology that has parallels in the rapid rise of AI. Clearly, AI can cause both harm and good.

For example, AI has been used in unfair automated decisions that impact minorities. And AI can be used for enhanced surveillance of human bodies and behaviour – something Huxley’s novel dramatises.

Additionally, AI can potentially damage the nonhuman world. Even the resources needed to run machine learning systems are associated with carbon emissions, e-waste and high water consumption.

And AI can also harm animals. For example, AI chatbots can mispresent animals or portray them as disgusting, worthless or killable. Also, steps are underway to harness automated farming systems in ways that might produce more intensive and inhumane animal farming.

But AI can also be used to help animals, such as by monitoring endangered species and replacing the need to use animals in medical experiments.

Politics & Society

AI apocalypse or overblown hype?

An opportunity for reflection

Spambots brings together AI, art and animals to promote engaged reflection about these important topics. As AI penetrates further into human and nonhuman lives, art is particularly important in revealing to us both the positive and negative potential of this powerful technology.

You can visit the Spambots at Science Gallery Melbourne. The NOT NATURAL exhibition is on until 29 June 2024.

Banner: Installation view of Spambots by Neil Mendoza (UK/USA) in Science Gallery Melbourne’s NOT NATURAL. (Matthew Stanton, 2024)