Treasure trove gathered from afar

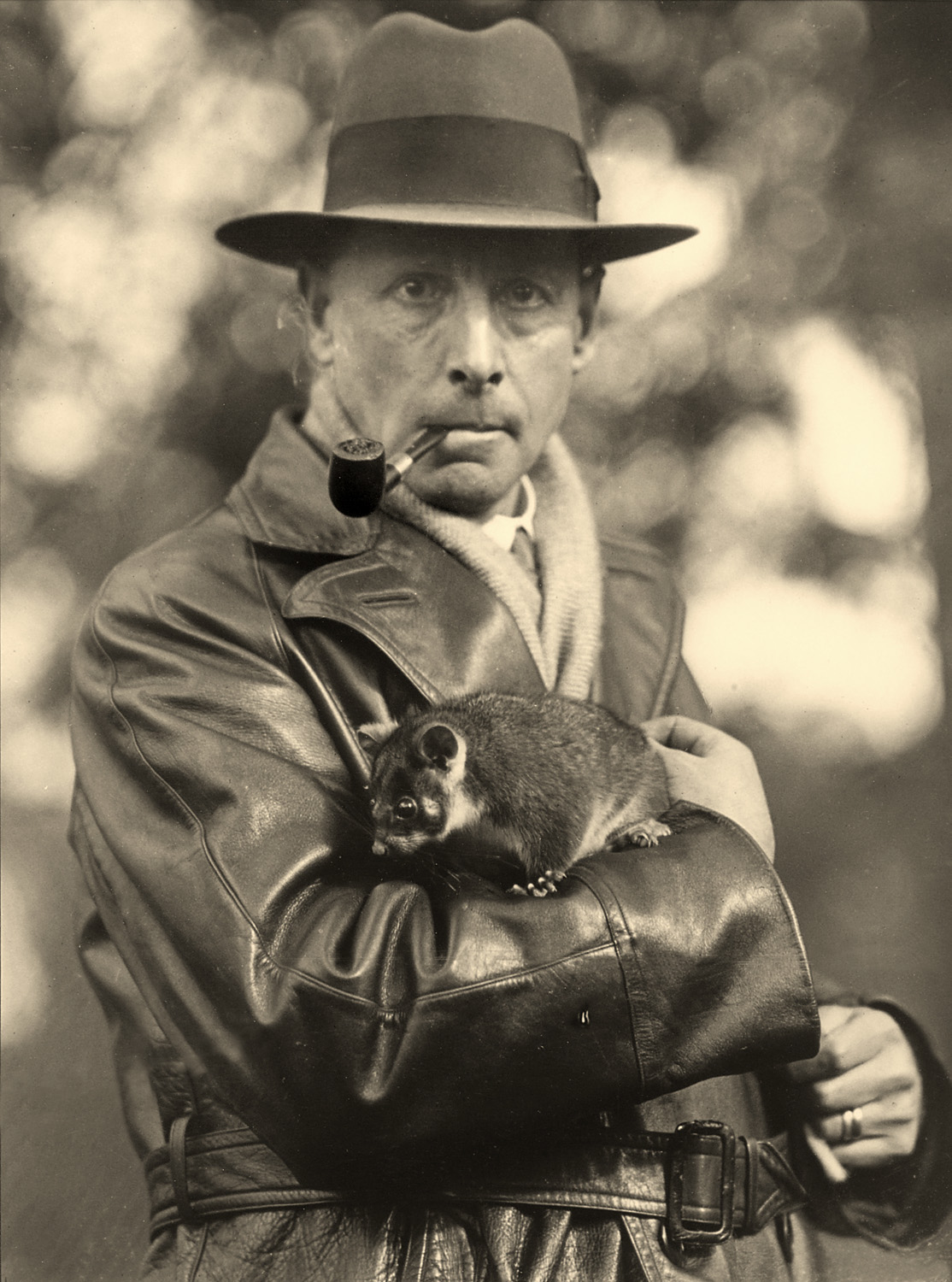

An Indiana Jones lookalike left 60 boxes to a University of Melbourne museum. Inside, researchers found a clue to the mystery of the museum’s mummified Egyptian head.

Published 19 August 2016

The jaw of a giant wombat and the skull of a Tasmanian Tiger, both extinct, are among the bones of a near 100-year-old collection at the University of Melbourne’s Harry Brookes Allen Museum of Anatomy and Pathology. But they aren’t the biggest surprises.

Among the 60 boxes being painstakingly catalogued for the first time, museum curator Dr Ryan Jefferies has found a mummified human hand. It could be the answer to the mystery of why in the museum’s basement storeroom lies the mummified head of a 2000-year-old ancient Egyptian.

The bones are part of the virtually forgotten specimen collection of English naturalist, anatomist and anthropologist Professor Frederic Wood Jones (1879-1954), who came to Australia in 1919 and joined the University of Melbourne as head of anatomy in 1930. Like many European naturalists, he was fascinated by Australia’s fauna and flora and built up a large collection of specimens. But early in his career, between 1907 and 1908, he had carried out archaeological survey work in southern Egypt to save ancient relics ahead of an expansion of the Aswan Dam that sits across the Nile.

Was the head discovered as part of that work and brought to Australia by Professor Wood Jones? We can’t be sure, but finding a mummified hand in the Wood Jones collection suggests it is the most likely explanation of how the head ended up in the museum.

“When we came across the hand and discovered what it was I went searching through the records of Wood Jones’ Egyptian survey work. I found a photograph of a mummified hand that looks remarkably like the one we have. So if he had brought back the hand, it is at least plausible that he may have brought back the head as well,” explains Dr Jefferies, who has an enthusiasm for bones and specimens going back to childhood. He learned taxidermy at just 14.

If Professor Wood Jones did in fact bring back the head, presumably for teaching purposes, the head is now teaching us far more than he would have ever imagined.

Using scanning, 3D printing and forensic science, a multi-disciplinary research team including Dr Jefferies has already reconstructed the face of the head, revealing it to be that of an 18 to 25-year-old woman they have named Meritamun.

Read more: Brought to life, 2000 years later

A copy of the head will be displayed at the museum, but they have also produced a 3D printout of the skull and a virtual reality rendering for students to investigate and test their forensic and diagnostic skills.

“It is a great opportunity to carry out forensic analysis and is an exciting teaching tool for students to understand pathology and apply it,” says Dr Jefferies.

Meritamun is one of 12,000 mostly human specimens at the museum. She is stored in an air-conditioned basement among sliding steel shelves. Here, preserved in formaldehyde solution, are organs and limbs going back more than 100 years. In one tall jar stands the hand and forearm of a soldier killed on the Western Front in WWI displaying deep shrapnel wounds.

Some institutions have started cremating their old specimen collections or putting them into permanent storage, believing there is little use for them in a world where the human body can be rendered on screen in detailed 3D. But Dr Jefferies says there is real value in having the actual specimens.

Irreplaceable

“When high school students come to the museum the first thing they all ask is whether the specimens are real. They can be a little taken aback at first but most are incredibly fascinated. People simply want to know what we look like, inside and out, especially at a time when most of us are very removed from the realities of death and dead bodies,” says Dr Jefferies.

“But the old specimens also can display unique examples of disease or damage, and as technology and investigative techniques develop, these specimens may still have much to tell us.”

They are also irreplaceable. While many people continue to generously donate their bodies to medicine, the specimens at the museum include rare pathology. “Not only is each specimen unique, but they were taken at a time when it was acceptable to take specimens without consent. Society attitudes have rightly moved on, but that means specimens today are much harder to obtain.”

It also means that the University is prepared to consider repatriating the head back to Egypt if deemed appropriate in the future. “There are important moral and ethical consideration to be aware of in handling all our specimens and it is a constant balancing act weighing those considerations against the educational value of preserving the specimens,” says Dr Jefferies.

The same technology and techniques that are being used to restore Meritamun are now being used by Dr Jefferies to give new relevance to the museum collection. A set of human lungs from the historical collection has been recreated on an advanced 3D printer in which the colours of the lungs have been reproduced in photographic detail for students to handle and study. Dr Jefferies is now experimenting with having organs printed out in malleable silicon to replicate the texture of organs.

“The technology means that students can use 3D virtual reality and print outs to understand tissue, bones and organs. Even surgeons can use them to practise on representations of the actual structures in a patient they will be operating on,” says Dr Jefferies. “So everything we are doing with Meritamun has an application in modern practice.”

The University of Melbourne’s Harry Brookes Allen Museum of Anatomy and Pathology is at the Medical Building, corner of Grattan Street and Royal Parade, Parkville, Melbourne. It is not open to the public, but tours cane be booked by tertiary and VCE students studying a relevant subject, academics and health professionals. Details here.

Banner Image: The Pyramids of Giza at sunset in 2015. Picture: David Degner/Getty Image.