Where have all the stars gone?

Stars helped shaped human culture for thousands of years, but we see far fewer of them now than our ancestors or rural friends; now a citizen science program will map light pollution across Australia

Published 19 June 2020

For life eternal, animals have lived under starlit night skies. Animals may use stars to navigate and for some species, the stars and the moon are the only light they see.

That was, until the evolution of humans and our recent industrialisation of much of the planet.

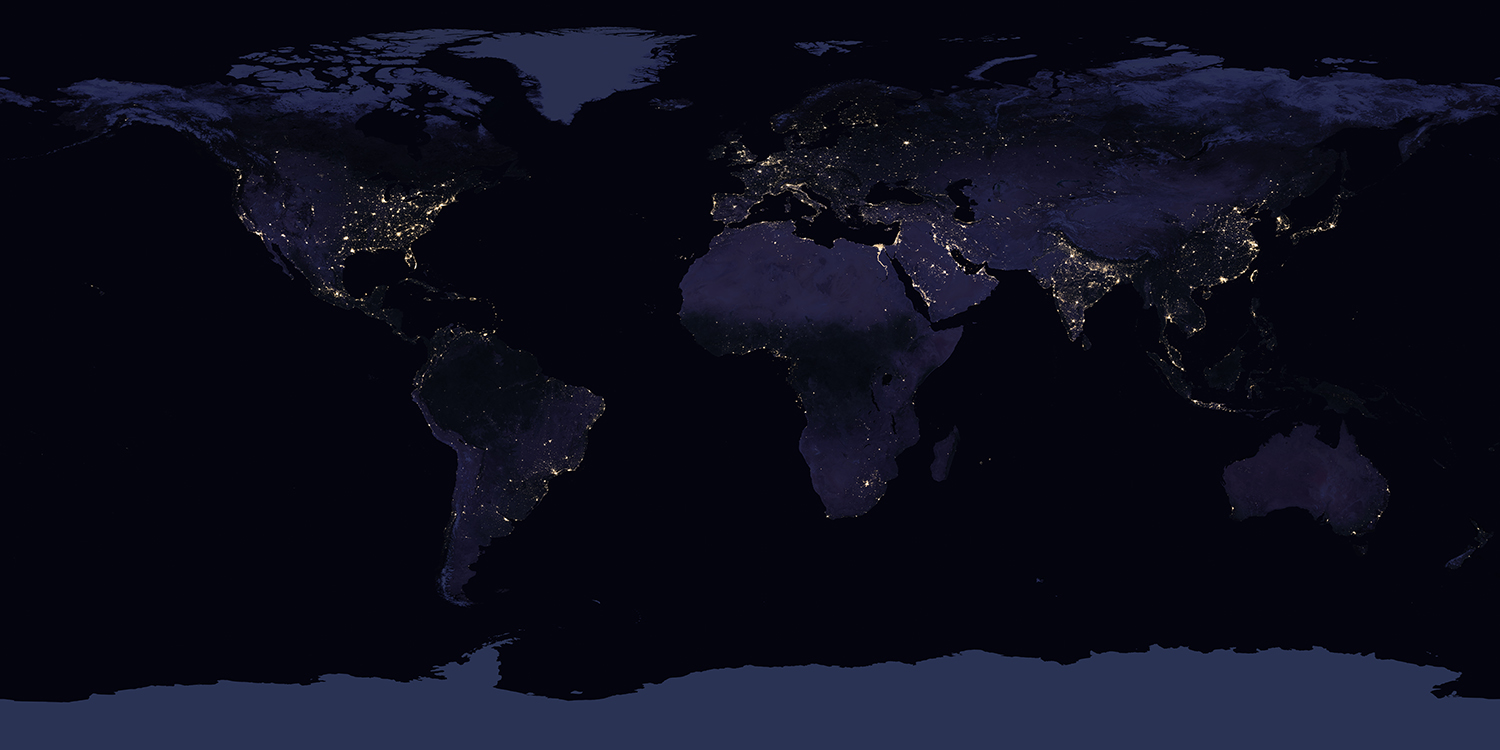

Today over 80 per cent of the world’s population lives in an urban environment and while city-dwellers may follow Stephen Hawking’s advice to look up at the stars, we see far fewer of them than our ancestors or rural friends.

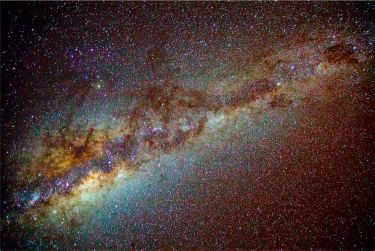

For most of us, the Milky Way is something we are sadly much more likely to see in photos than with our own eyes.

What has happened to the stars?

Of course they’re still there, but we can’t see them because of light pollution: the excessive and misdirected anthropogenic and artificial light that has invaded our night skies.

Stars have helped shaped human culture for thousands of years. For example, the great Emu in the Sky is an Aboriginal Australian constellation composed of the dark patches of the Milky Way – the space between the stars.

Its orientation is a sign of the time to hunt for emus or collect their eggs. This important part of indigenous culture and heritage is disappearing, and disappearing fast, as light spills from our urban streets into the surrounding countryside.

Today the familiar skyglow that forms the backdrop to our urban environments can reach more than 30 kilometres beyond the last working streetlight.

This loss of the night sky has dramatic consequences, and not just because it pushes astronomical observatories that depend on pristine, unpolluted skies further into the interior of the country.

Research suggests artificial light has negative effects on human health, increasing risks for sleep disturbances, obesity, diabetes and certain cancers. The lights we have installed in our homes and streets have shifted a delicate biological balance – we sleep for less time and we sleep less deeply.

Even short periods of exposure to very dim light (less than that produced by your bed side lamp) can reduce melatonin concentrations in our bodies by 50 percent.

Sciences & Technology

Indigenous astronomy

This is critical as melatonin plays a vital role in maintaining our sleep-wake cycles, but it’s also a powerful antioxidant. As melatonin levels fall, our important sleep is disrupted and our chance to combat disease is reduced.

And it’s not just humans who suffer.

Animals that remain in our cities have disrupted sleep, increased stress and must change their behaviours to accommodate the loss of darkness.

The biggest problem we face is that we are only just beginning to understand the magnitude of light pollution.

By measuring the light that reflects back up from the earth into space, we can create light pollution maps. But these maps can’t tell us what light pollution looks like from the ground.

To solve a problem, we must first be aware of it. People tend to be far more aware of air and plastic pollution, but light pollution is comparatively much easier for us to solve.

The Globe at Night program is an international citizen-science campaign that seeks to raise public awareness of the impact of light pollution by inviting citizen-scientists to measure their night sky brightness and submit their observations from a computer or smart phone.

The program has generated over 11,000 observations to date but there remain large global gaps; Australia is one of them.

Sciences & Technology

Putting the Universe under the telescope

#WorldRecordLight, a citizen science challenge, aims to close this gap and at the same time will attempt to break a world record for the largest number of people participating in an online sustainability lesson.

To break the record in 2020, at least 2,000 people will need to register and take part in the online lesson on light pollution and its impact, answering some questions and, finally, recording their own night sky observation.

So, let’s not look down at our feet; but to the skies, and try and make sense of what we see or perhaps more importantly, what we cannot see.

Light pollution is easily solved by flicking a switch, but people are far more willing to act if they understand how serious a problem light pollution is.

Together we can make a difference.

#WorldRecordLight is held from 1pm AEST on Sunday June 21st 2020 - the longest night of the year in the southern hemisphere. The challenge will last 24 hours, giving everyone ample time to participate in this family-friendly half-hour lesson.

The initiative is been co-driven by the Australasian Dark Sky Alliance (ADSA) and the Department of Agriculture, Water and Environment, but anyone with internet access around the world can participate.

Banner: Getty Images