Why we need to use water desalination plants early

Turning on the Wonthaggi water desalination plant now rather than later will save money in the long run and head off an emergency later

Published 21 March 2019

The long dry has left Melbourne’s water supplies at their lowest levels since 2011, at less than 55 per cent capacity. In response the Victorian government has made the largest-ever water order from the desalination plant at Wonthaggi.

This is a good decision.

Running the Wonthaggi desalination plant is a high cost option in the short term, but it will end up saving Victorians a lot of money. Despite the relatively high price tag of desalination, it will actually reduce the cost of maintaining reliable water supplies for Melbourne.

We’ve modelled Melbourne’s water supply system using a range of scenarios that examined the risks posed by drought. Under recent storage conditions, we found that using the desalination plant more often will save about $250 million compared with only using the plant in emergencies.

The money is saved because, by operating the desalination plant when storages are at higher levels, rather than waiting until they are dangerously low, you can create a large enough buffer of stored water to head off emergencies. Without a sufficient buffer, we run a high risk of having to spend a lot of money in building emergency expansions in desalination capacity to stop Melbourne running out of water.

Just last year, Cape Town in South faced a water emergency where it was forced to ration water. If it wasn’t for timely winter rains that stopped the reservoirs going dry, Cape Town’s entire water supply system would have faced being turned off. In contrast, here in Victoria, when faced with the real possibility of storages falling empty because of the Millennial drought (2001-2009), the Wonthaggi desalination plant was built and other emergency water saving measures and augmentations were undertaken.

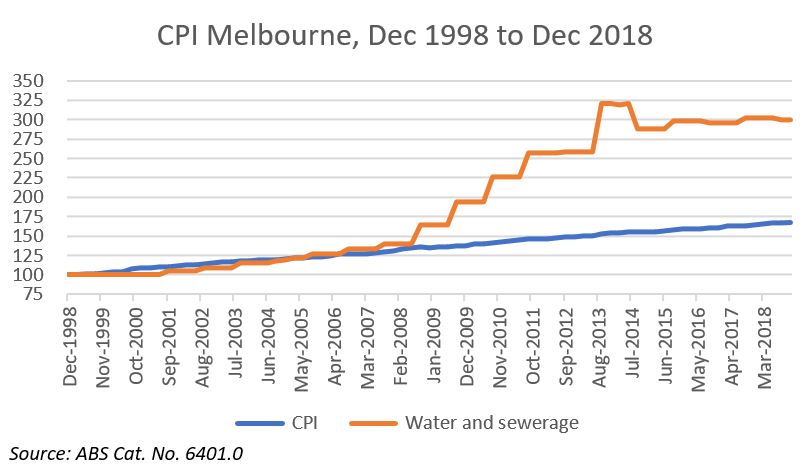

With only about a years supply of water in storage, these were critical emergency augmentations but they cost a lot of money and as a result the cost of water rose dramatically. Before the investments, the cost of water and sewerage services in Melbourne had been pretty consistent for most of the time that the ABS has tracked it. However, between December 2007 and December 2013 the cost of water and sewage skyrocketed by 129 per cent compared with just a 17 per cent rise in Melbourne’s consumer price index, which is a general measure of the cost of goods and services.

But our simulations found that the likelihood of having to build more expansions to the water supply system to avoid a Cape Town-like emergency is halved when the desalination plant is turned on at times of higher storage levels, rather waiting for an emergency. So, the order for 125 gigalitres from the desalination plant is a sensible decision that will save money in the long run. The government has said the order will increase the annual cost of water to households by $10.

Of course money could be saved in the short term by not operating the plant, but the longer term risk is that more money will have to be spent later to expand the plant to cope with an emergency situation that could have been avoided.

Sciences & Technology

Will water ever be worth more than oil?

In Melbourne, water reliability is now underpinned by a range of actions beyond just the high cost of desalination. These include: trading water in the market, harvesting stormwater, and implementing demand management actions, all of which need to be focused on. But the key benefit of using the desalination plant is that it can ensure we have that buffer in water supplies.

Our research showed that the total expected cost of meeting projected demand in Victoria, based on rainfall inflows into the dams similar to those over the last twenty years, ranges from about $250 million to almost $1.85 billion, in net present value terms, over a 20 year timeframe. That wide range is because the final cost is dependent on how much water is in storage at any one time. The more water in storage, the cheaper it is to reliably meet demand.

When water storages are high, the value of that stored water stems from it helping to defer the operation of the desalination plant. As storages fall, the value of turning on the desalination plant early is that we can avoid an emergency and the associated costs of having to augment the water supply system. It also means we can reduce the cost to society and the economy from having to impose water restrictions.

If we don’t want Melbourne to suffer the crippling water shortages that Cape Town has recently experienced, we need to invest in maintaining high levels of water in storage.

Banner image: The Yan Yean Reservoir in Victoria, pictured in 2009. Mark Dadswell/Getty Images