Animation in the 80s: the view from Melbourne

Making an animated film has never been easy, but in the 1980s it seemed the artform’s future was bright

Published 24 May 2016

In the era of Pixar and Aardman it would be easy to take animated films for granted. But it wasn’t always around, and its evolution in Australia has been complex.

Two of the films embedded in this article – Pleasure Domes by Maggie Fooke (1987) and my own student film, Still Flying (1988) – were produced during the 1980s at what is now Australia’s longest-running film school; it started life at the Swinburne Institute of Technology in 1966 and in 1992 transferred to its current home at the University of Melbourne’s Faculty of the Victorian College of the Arts and Melbourne Conservatorium of Music.

To mark the school’s golden anniversary, some 50 films are being made available to the public for the first time which, in my case, offers a chance to reflect more broadly on animation in the 1980s.

Growing up

Growing up as a television addict during the 70s I saw most Australian animation in the form of television commercials such as Mr Sheen, Louie the Fly, Norm from Life Be In It and IC POTA.

Although agnostic, I loved watching the animated Christian Television Association commercials with their cartoony blend of irony and virtue.

In 1976 Bruce Petty’s animated film Leisure picked up an Academy Award, and in 1977 the Yoram Gross feature film Dot and the Kangaroo had a local cinema release. But there was little else out there in terms of original Australian animation visible to the broader public.

Animation Studios in Sydney such as API, Hannah-Barbera Australia and Burbank were busy but most of the films by these studios were generic adaptations of classic stories such as Swiss Family Robinson and Treasure Island, paid for by entertainment companies in the USA to create budget-priced telemovies and direct-to-video material in the new home-video entertainment market.

In 1981 Australian filmmakers Alex Stitt and Phillip Adams created the ambitious, animated feature Grendel Grendel Grendel. It didn’t look or sound like any Disney movie and the design was reminiscent of Alex Stitt’s television commercials, such as Life Be In It.

It was highly stylised and bold but what it did have in common with the previous decade was a fascination with classic stories, in this case Beowulf.

I was exposed to short films made by independent filmmakers and students for the first time at the now-defunct Melbourne State College and later at the original Swinburne School of Film and Television.

Most aimed at an adult audience. These were personal, insightful, bizarre, experimental, provocative, humorous and sometimes puzzling films that often ditched the so-called rules of filmmaking, design and storytelling, either out of a mistrust of filmic orthodoxy or simply not knowing. Teachers would show locally-made films sourced from the State Film Centre (now ACMI) and others from their extensive school archives.

I was inspired by the humour and poetry of former Swinburne student animators including Dennis Tupicoff, John Skibinski, Sabrina Schmidt, Peter Viska, Maggie Fooke, Glen Melenhorst, Ann Shenfield, Steve French, Noel Richards and many others, all of whom progressed into continuing as professional independent filmmakers, set up their own animation companies or worked for emerging animation studios of the 80s such as Funny Farm and Video Paint Brush.

The old Swinburne film school, together with the media courses at La Trobe University and teachers colleges such as Melbourne State and Rusden were an active intertwining culture of production activity where many things became possible. In the 80s, making animation on video, Super-8 or 16mm film was an expensive endeavour but tertiary institutions had equipment, instructors and technical support that no 18-year-old could normally get their hands on.

Today, of course, it is not unusual for a student to have a computer better than the one supplied by the university. That, in addition to free open-source animation software, means getting an animated film made, at least technically, is easier than ever.

Once graduated, animation students either went knocking on studio doors or headed to the Australian Film Commission (AFC) for a grant. These days Screen Australia regards short films as a “stepping-stone” to a feature film or TV series. But the in the 80s and 90s the AFC regarded the short as a form in its own right and actively supported short-filmmaking including animation and experimental.

This fostered a great number of animations that made their way into film festivals in countries that had rarely if ever seen an Australian animated film before.

In 1983 Dennis Tupicoff’s Dance of Death won the jury prize at Cracow Short Film Festival and also an AFI award back home.

The Melbourne International Film Festival was one of the few places in the early 80s to get an animated film screened.

In 1983, the St Kilda Film Festival defined itself as a festival that only screened short films and this triggered the emergence of more Australian short-film festivals into the early 90s, when Flickerfest and Tropfest kicked off.

Making headway

Towards the end of the 80s, it looked as if Australian animation production was making headway into television. In 1989, I was invited by the Australian Children’s Television Foundation (ACTF) to attend a weekend creative conference of new and established writers, illustrators, musicians, puppeteers and animators.

The foundation was looking to harvest ideas for a new a pre-school TV series that eventually became Lift Off. This summed up the decade – producers could see the varied and available wave of new artists and together with experienced practitioners embraced them to search for new ideas, characters and stories.

They began to produce the animated series The Greatest Tune on Earth, and had engaged independent animators and studios to contribute to programs such as Kaboodle for ABC TV, a collection of animated short films for kids. Animated shorts for adults also found a home on Eat Carpet, the late night SBS anthology of independent short films, now sadly defunct.

Making an animated film has always been a precarious business, but a lot looked possible during the 1980s.

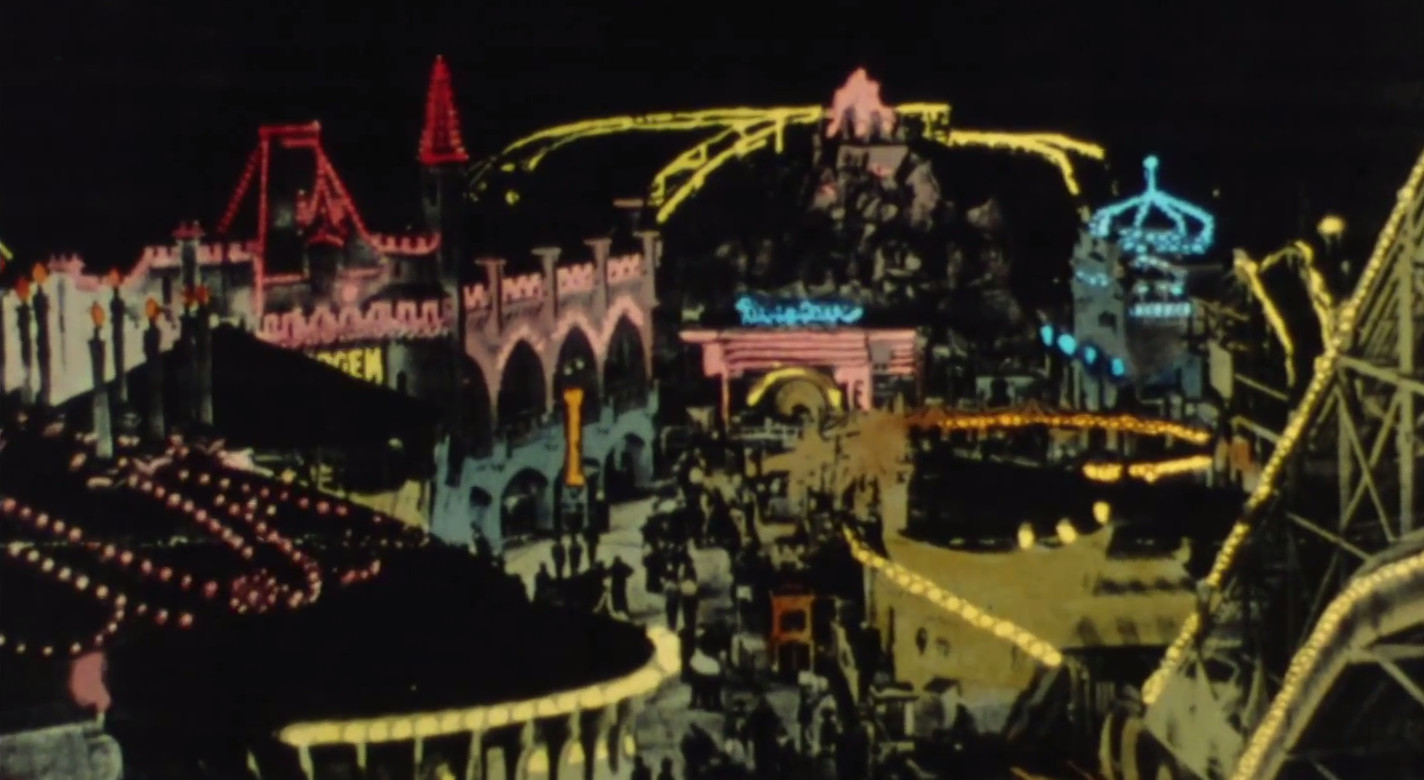

Banner image: Still from Pleasure Domes. 1987. Maggie Fooke.

This is the fourth article in a series to mark the Golden Anniversary of Film and Television at the Victorian College of the Arts. See Part One, Part Two, Part Three and Part Five. Visit the Film and Television 50th Anniversary website and Digital Archive website for more information.

A number of films by students at the VCA will be shown at the 2016 Melbourne International Animation Festival, 19-26 June. Details here.