Cool All at Onceness: Australian film in the 1960s

Ian Baker’s film, shot while a student, reveals much about the era in which it was made

Published 13 May 2016

Roxanne, Japanese Story, Evan Almighty …

If you watch film, chances are you’ll be familiar – even unwittingly – with the work of Melbourne’s Ian Baker. As one of Australia’s most highly-regarded and talented cinematographers, and a long-term collaborator with the director Fred Schepisi, he has shot a great many feature films and television series all over the world.

But chances are even higher you’ve never seen the film Baker shot while a film student at Swinburne in the 1960s. That film school, which began life in 1966, relocated in 1992 to its current home at the University of Melbourne’s Victorian College of the Arts, and is currently celebrating its golden anniversary.

To mark that anniversary, Baker’s student film is one of 50 that will be made available for free for the first time in the coming weeks, as part of an ongoing Digital Archive project.

And it’s certainly worth taking a look at.

A context of cool

Cool All at Onceness was made in 1968, when Baker was 19.

At that time, industry lobby groups were agitating for Commonwealth support for a local film industry. The production sector was grounded in industrial, public relations, training and commercials production, underpinned by regulations in 1960 mandating 100 per cent television and cinema commercials screened in Australia were to be made by Australian companies and crews.

The ambition for creative Australian content was informed by a tradition of cultural nationalism dating back to the 1890s, promoted by the Left, and a growing disdain for American commodity culture.

Activist and experimental “underground movies” – as has been pointed out by authors such as Peter Mudie and Albie Thoms – articulated an even more radical resistance to the heavy-handed censorship and conformism of the period.

By 1968, avant-garde creative practice in painting, theatre, music and film was well-established and was directed against, among other things, the American war in Vietnam.

This “alternative” sensibility was far more ambivalent about commodity culture, and used it ironically in mash-ups and pastiche.

Riffing on marshall mcluhan

Cool All at Onceness is infused with this ambivalence. In 1964, under the National Service Act, compulsory National Service was introduced for 20-year-old males in Australia. Had Baker been called up in 1969 he would have been legally obliged to spend two years in the army, possibly in Vietnam – a prospect that no doubt focused the mind.

Canadian media critic and “guru” Marshall McLuhan was among the thinkers in this era whose writing nourished hope, by promoting so-called alternative world-views and “radical” lifestyles.

The ideas he’d expressed in his books The Gutenberg Galaxy (1962) and Understanding Media (1964) were re-purposed and condensed for his 1967 bestseller The Medium is the Massage, in which he explores, among other ideas, the nature of media and the role of technology in our lives.

Baker’s film, coming in at just under five minutes, is an audio-visual essay riffing on McLuhan.

The opening scene exposes the industrial production of the television presenter (a move nowadays known as “self-reflexivity”) as the camera pulls back to reveal the studio in which a presenter (played by graphic arts student Andrew Clark) is established as a TV “talking head”, narrating texts from McLuhan.

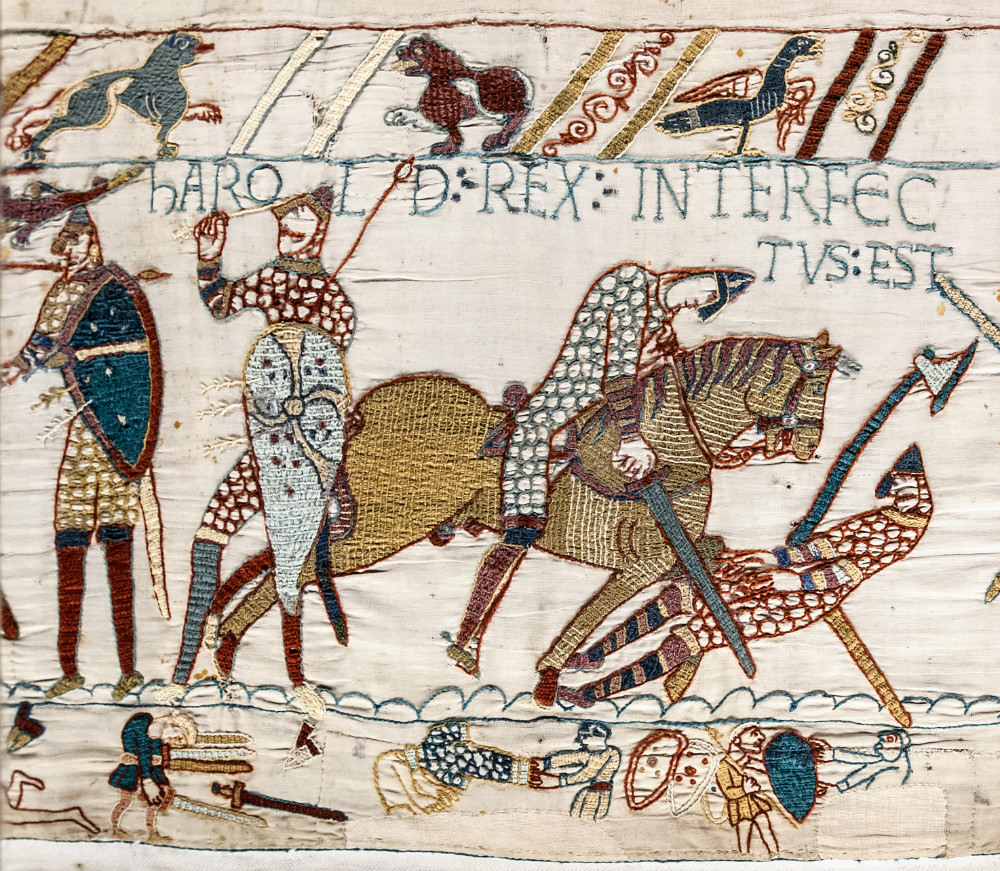

Baker’s allusion to war is oblique: the second sequence of the film uses graphics to illustrate McLuhan’s texts with images from the 11th-century Bayeux Tapestry, often considered the earliest art depicting in detail the horrors of war.

Not so fallow

Contrary to received wisdom, the “fallow” 1960s nurtured a creatively ambitious and internationally informed film culture in Melbourne, as can be seen in the 2003 documentary Carlton + Godard = Cinema by veteran Swinburne staff member Nigel Buesst; in films by Giorgio Mangiamele; in essays by Adrian Danks and Adrian Martin.

The city’s film societies and festivals were among the most active in the world, partly because UK and US commercial, distribution and exhibition made it difficult for audiences to access world cinema otherwise.

It was a period in which – despite a functioning film production sector making sponsored “utility films” for industry, and factual film and documentary for government – very few independent features were made. Those that were found the road to cinematic release blocked by the UK and American distribution and exhibition duopoly.

Cecil Holmes’ feature film Three in One (1957), for instance, was praised in Edinburgh, sold into the USA, China, Sweden and France, but was not released theatrically in Australia. Instead, Ken Hall bought the film for Channel 9.

The ABC made Skippy the Bush Kangaroo (1966-68), and Crawford Productions in Melbourne made the highly successful police drama Homicide(1964-75), then Hunter (1967-69), and later Division 4 (1969-1976). But 97% of drama on Australian television in the late 1960s was American.

Agitation

The writer Sylvia Lawson was one of those agitating for an Australian feature industry. In the pages of Nation, she pointed out that “they make films in Nkrumah’s Ghana, Soekarno’s Indonesian and Castro’s Cuba. But not in Menzies Australia …”. It was a period in which filmmakers such as Cecil Holmes and Ken Coldicutt were secretly blacklisted from Commonwealth film units because they were “adversely known” in the eyes of ASIO.

On the industrial front, independent producers, writers and directors organised with trade unions and Guilds representing actors and technicians in the TV Make it Australian campaign, seeking regulation to support Australian content on commercial TV. The success of that campaign has underpinned Australian drama production for decades.

Film historian Ina Bertrand, in her 1989 book Cinema in Australia – A Documentary History, described the climate of the 1960s as one “in which the government of the day could expect to win some esteem by launching an arts assistance programme with provision for film”.

And that view seemed to hold some sway.

By May 1969 the Film and Television Committee of the Australian Council for the Arts, initiated by “Nugget” Coombs, had proposed concrete mechanisms for a Film Development Fund, a film school (later AFTRS), and an Experimental Film Fund.

Those initiatives were loudly derided by the “trade” establishment and the conservative press, but an infrastructure had at last been established that enabled talented and determined filmmakers to build a life’s work around film and television in Australia.

Cool All at Onceness nurtures the seeds of all this, and is infused, inevitably, with the rebellious spirit of ‘68.

I would encourage you to watch it.

Banner image: Still from Cool All At Onceness (1968). Ian Baker.

This is the second article in a series to mark 50 years of filmmaking at Australia’s longest-running film school. See Part One, Part Three, Part Four and Part Five. Visit the Film and Television 50th Anniversary website and Digital Archive website for more information.