Film in 1970s Melbourne — the enduring human drama

Every human being has a story to tell, but these three student films from the 1970s offer lessons that go way beyond the individual

Published 17 May 2016

In grouping films by decades, it’s crucial to note the labels “quiet 50s”, “turbulent 60s”, “hangover 70s” and so on, are at best generalisations.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of Australia’s longest-running film and television school. Starting life in Swinburne Institute of Technology, the school moved to its current home at the University of Melbourne’s Victorian College of the Arts in 1992.

As selected student films from the school’s archive are released, decade by decade, for an ongoing Digital Archive project, I was invited to look at some of the school’s films from the 1970s, among them my own, shot while I was completing a one-year diploma in film in 1979.

To understand the 1970s it helps to reflect upon the two decades that came before. The 60s exploded out of the so called “quiet” 50s, when youth seemingly turned against suburbia, marched against the Vietnam war, and were imbued with visions of remaking the social order. The ideals of the 60s can be seen as culminating in the 1972 election of the Whitlam Government. Heady times.

The big man set out to deliver. He succeeded in part, but crashed when the real 1970s caught up with him – a kind of collective hangover and reorientation from the turbulent times that preceded it.

This context is critical to understanding the types of stories that began to emerge in the 1970s. The cultural shifts of the 60s set it up, triggering a desire among filmmakers, playwrights and writers to challenge the cultural cringe, and Australia’s over-reliance on stories produced elsewhere – in particular, the USA and Europe.

We yearned to focus, instead, on Australian stories, told by uniquely Australian voices, and we were prepared to experiment in a search for new ways to tell the stories.

The themes marked a return to that which had not changed, and were driven by an understanding that there were Australians who had missed out on the excitement, people still living lives of quiet desperation in suburbia.

Artists were also in search of stories that documented the overlooked individuality and creativity being expressed in the suburbs. After all, that’s where most Australians lived. The artist’s eye was also drawn to those who struggled at the margins, the outsiders, the alienated, especially among the youth sub cultures – as storytellers we were in search of unique characters, and unsung lives.

The roof needs mowing

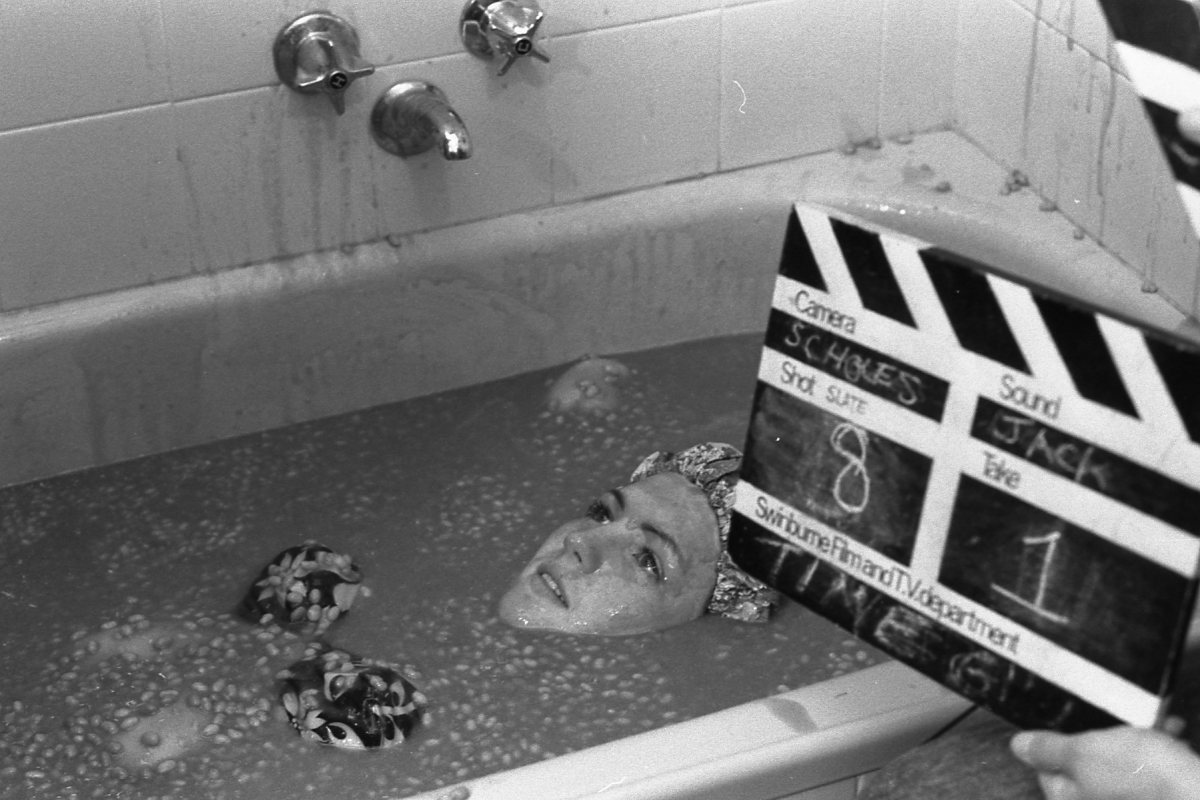

Award-winning director Gillian Armstrong’s student short, The Roof Needs Mowing (1971), sits neatly between the two decades. It has something of the romance, energy and youthful optimism of the 60s: Armstrong was drawn towards recording, as one critic put it, “the magic in everyday life”. But there is also a darker subterranean current in her work, one that hints at suburban boredom, disorientation and regret, albeit expressed with whimsy and a light touch.

Mind you, Armstrong has a young couple bathing in a bathtub filled with the beans, and a middle-aged man stuck in a rowing boat within the pool.

The Roof Needs Mowing heralds the distinctive, eccentric vision of a filmmaker who has sought to balance bold, edgy feature films with documentaries concerned with social issues – Armstrong’s stories are driven by a deep affection for her wide range of characters, both contemporary and historical, and a deep empathy for human fragility.

George and needles

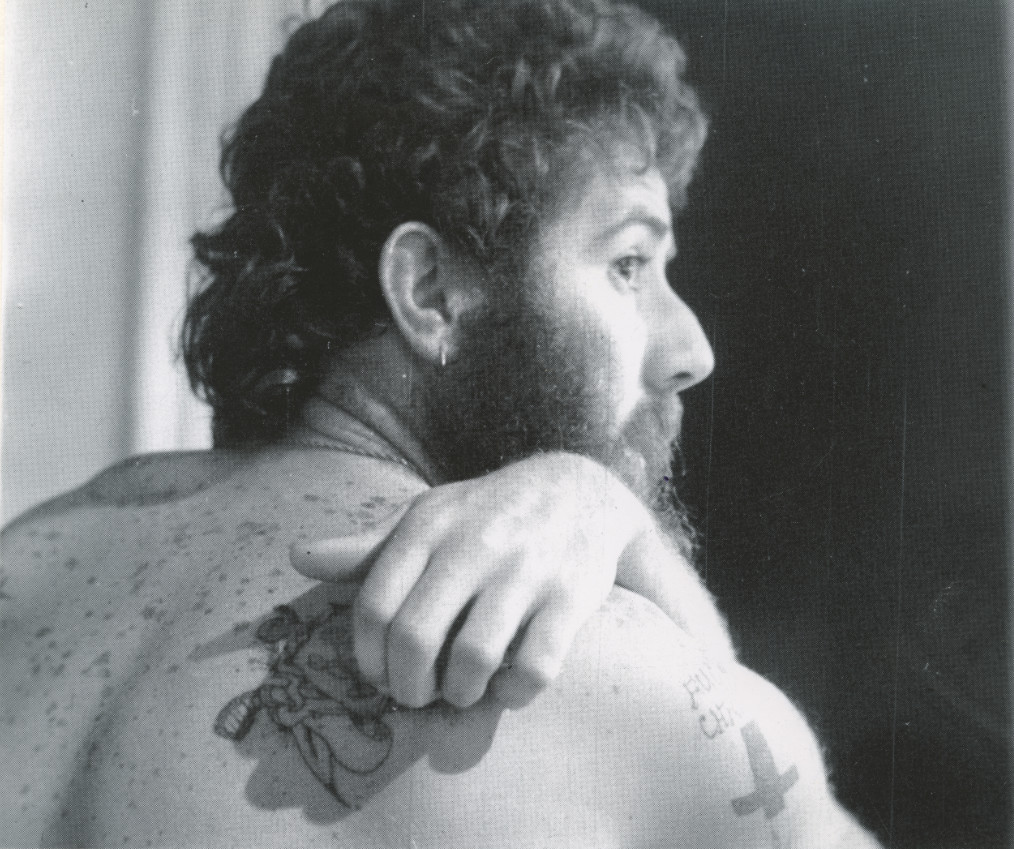

Greg Dee’s groundbreaking George and Needles (1972), bears some striking similarities with Armstrong’s short. It is also shot in black and white, and driven by an edgy, youthful energy. He too employs a restless roaming camera, which lights on telling details: a table littered with beer bottles, the worn furniture of a shared household, sturdy frayed work-boots tapping out the rhythms of the guitar player.

But Dee’s film is more confronting, more frenetic in its pace, and more disturbing in its uncensored, gritty, realistic portrait of two directionless young men engaged in erratic, beer-fueled conversations over drink, under the bloody tattoo needle, and over music.

When the two men sing the blues, it is an anguished howl. They speak the uninhibited language of alienation and disaffection. The 60s are well and truly gone, and in its place there is confusion and a simmering anger.

Glenn’s story

As already mentioned, I was privileged to do a one-year diploma in film at the tail end of the decade, when the film and television school was still located in Swinburne Institute of Technology. I was drawn to Glenn’s Story, based on a one-page piece, penned by a 15-year-old boy in a writing class.

That class was run by my friend, Sue Dunstan, in Poplar House, the maximum security unit of the Turana Juvenile Detention Centre – an institution of the Victorian Welfare Department. When she showed me Glenn’s piece, I immediately saw that it could form the basis of a poignant documentary.

I was struck by the simple eloquence of the piece, the scope it covered in so few words, and by one of the opening lines, “Life wasn’t meant to be easy”, quoting the words of the man who succeeded, indeed overthrew, big Gough – Malcolm Fraser.

The film was conceived and shot within days on a budget of less than $1,500. The course lecturer, accomplished filmmaker Nigel Buesst, acted as mentor and cameraman. We were permitted by the relevant authorities to have Glenn read the piece as the voiceover, and to film inside the centre, and to crouch in “the isolator”, the tiny solitary confinement cell while Glenn re-enacted the horror of pacing the cell like a caged animal, pounding the walls, high window, and finally sinking to the floor cursing, “I wish I was never born”.

I recall vividly the intensity of Glenn’s re-enactment. This scene is followed by close-up shots of some of the incarcerated boys – staring straight at the camera, among them Indigenous kids. Those faces are as haunting and confronting today as they were then. Each one cries out for a story to be told.

With hindsight we come to understand that the human drama is always complex and diverse. There are always so many tales to tell, and many ways to tell them. We see that social injustice persists, and that there are many unsung voices aching to be heard, and many sub-cultures, awaiting recognition and documentation.

To reprise the Carl Jung quote I placed at the beginning of the film: “Every human being has a story to tell, and it is the denial of this story that leads to torment and discord.”

Banner image: Kurt Bacuschardt/Flickr

This is the third article in a series to mark the Golden Anniversary of Film and Television at the Victorian College of the Arts. See Part One, Part Two, Part Four and Part Five. Visit the Film and Television 50th Anniversary website and Digital Archive website for more information.