‘How we bring Indigenous knowledges into the academy is as important as the knowledge itself’

A new truth-telling book shines a light on the past, present and future of the University of Melbourne’s Indigenous cultural collections

Published 12 August 2025

The University of Melbourne holds some of the finest and most historically important collections of Australian Indigenous art and cultural material in the world.

But for years, many of these collections have remained largely hidden from public view – kept for teaching or research purposes, ignored, or, in at least one case, hidden in the basement to keep them from their legitimate owners.

The University’s new truth telling book, Dhoombak Goobgoowana Volume 2: Voice, describes the complicated history of these collections, the ongoing work to properly catalogue and digitise them, and efforts to reconnect – and in some cases repatriate – them to the Indigenous communities they came from.

Whether it is the incongruity of Aboriginal stone tools in a dental museum, the indignity of a collection of stolen human remains ‘lost’ in a basement, or the inspiring sight of people visiting the collection to see work created by their ancestors, the items below help illustrate the history, present and future of these collections.

However, these are but four of the innumerable untold stories contained in these collections.

‘Indigenous Art Collections at the University of Melbourne’ is a publication waiting to be researched and written.Susan Lowish – ‘Collections and Connections’, in Dhoombak Goobgoowana Volume 2: Voice

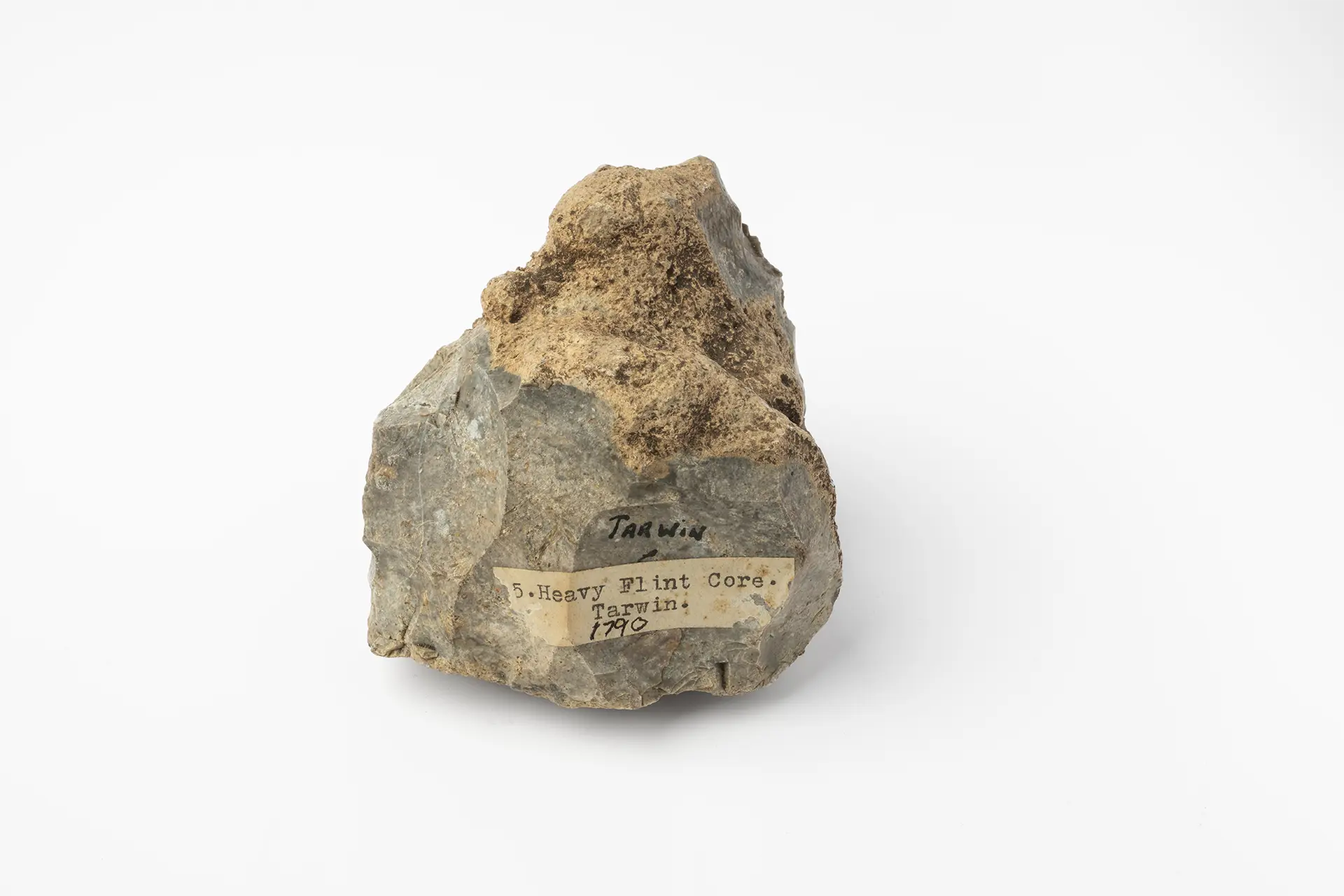

How did Aboriginal stone tools appear in a dental museum display?

From the chapter, Henry Atkinson Dental Museum Collection, Stone Tools, by Dr Jacqueline Healy

In the Henry Forman Atkinson Dental Museum, there are stone tools collected from various parts of Australia, with over eighty listed. They include ground-edge axes, points, flakes, flints, grinding stones, millstones, scrapers and hammer stones.

The stone tools were on display at the new Dental Hospital and Dental School when it opened in 1963.

In a building which for the Dental School and hospital was viewed at the beginning of a new era of modernity, the stone tools were interpreted as examples of a ‘stone age’ culture.

The source of the collection – that is, who collected and gifted the items – was not recorded.

During preparation for Dhoombak Goobgoowana, a file was located titled ‘museum’ that contained labels from a past museum display relating to “Australian aborigines”, which also include a list of the stone tools.

One of the labels in the file stated that: “These exhibits were part of the collection of the late Dr. Ramsay Smith and Dr. Cecil Madden. Presented by Mr. Cecil Madden B.D.S. of Adelaide.”

The name “Madden” was a a typo, and it now has been established that the stone collection was associated with Dr Cecil Boase Maddern and probably gifted after his death in 1957 by his son.

Questions remain, however, concerning the circumstances of the gift and the source of the stone tools. These connections we are still seeking to find.

The outcome of this process will be to seek advice from the Traditional Owners of the land where these stone tools were collected. Traditional Owners will be engaged in a consultation process to determine the future location and use of the collection.

A stolen skull in a glass case

From the chapter, Corrosive Collecting, by Rohan Long and Dr Jacqueline Healy

Students studying medicine in the 1960s recall anatomy lecturers boasting that the University of Melbourne had “the best collection of Aboriginal skeletons in the world”.

During this era, Aboriginal remains were still occasionally included in museum displays, possibly due to their sheer abundance in the building.

In a photograph of the Anatomy Museum from 1962, a Victorian Aboriginal skull from the Berry Collection can be seen displayed in a cabinet illustrating the concept of “blood vessels in bone”.

The skull is only identifiable as Indigenous by a numeric code inked onto the frontal bone; it’s not clear from the photograph whether it was labelled as such or displayed as an anonymous human skull.

In September 2002, the Berry Collection was unexpectedly uncovered in a locked basement storeroom in the Medical Building. The University contacted Aboriginal Affairs Victoria, which ordered the transfer of the collection to Melbourne Museum within three days.

Museums Victoria recorded over 800 Aboriginal human remains received from the Berry Collection.

The biganga – a visual reminder of unceded place

From the chapter, Returns Ablaze, by Associate Professor Sally Treloyn and Tiriki Onus

In 2017, the Wilin Centre for Indigenous Arts and Cultural Development launched the Research Unit for Indigenous Arts and Cultures (RUIAC).

A biganga (possum) skin cloak was crafted at the first RUIAC symposium as a foundational document.

Describing their motivation for creating the cloak, the team behind it wrote: “The responsibilities of Indigenous knowledges are situated with the holders of the knowledge.

“A responsibility shared and maintained, given space and given authority, the biganga represents diplomacies, relationships, scholarship and practices.

“The biganga plays a ceremonial role in the Faculty of Fine Arts and Music at the University of Melbourne, a visual reminder of unceded place, of Indigenous knowledges and relationships from close and distant nations, and memories and moments of diplomacies enacted at the time and into the future.”

Reuniting a collection with its origins

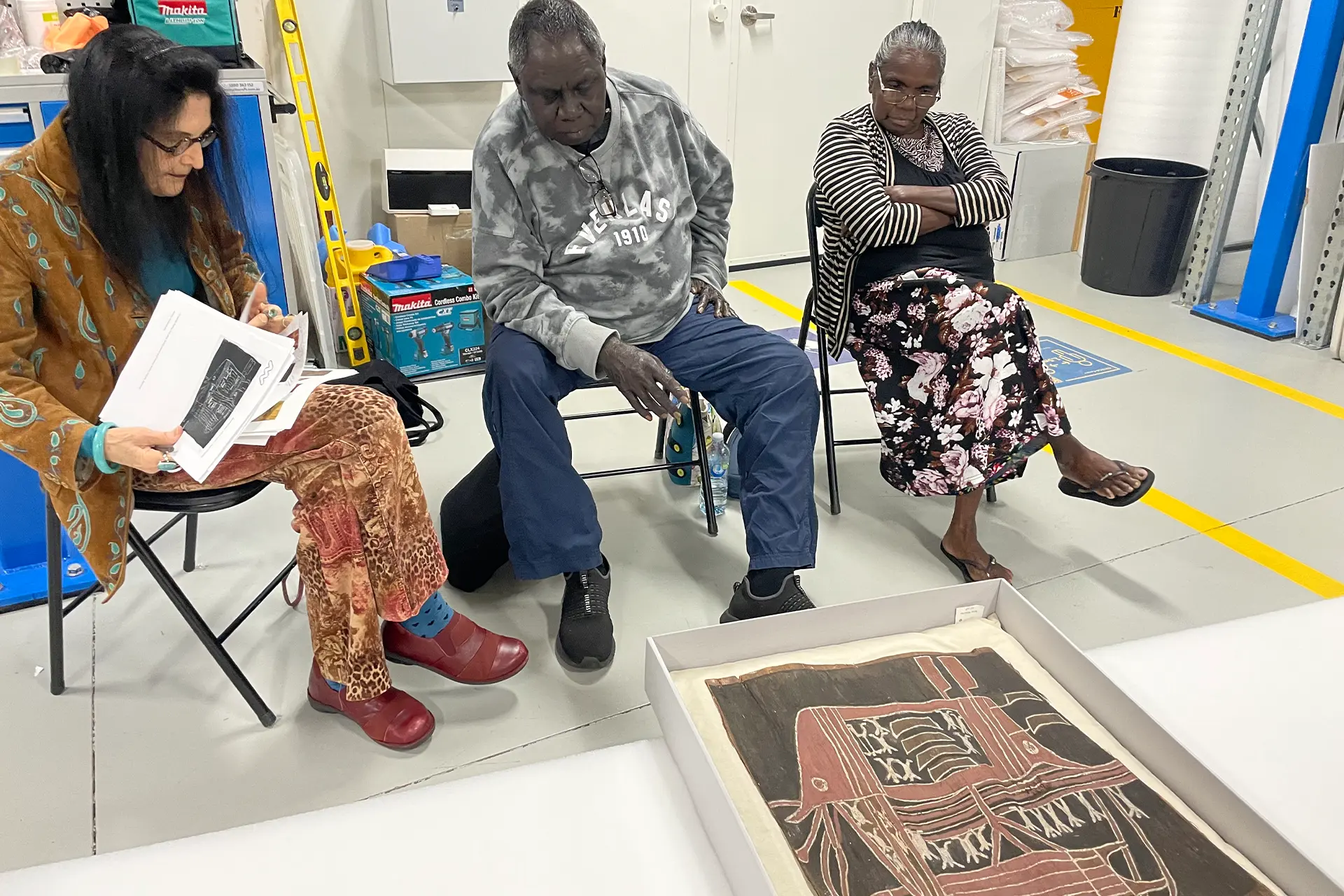

From the chapter, The Donald Thomson Collection, by Louise Murray and Professor Marcia Langton AO

The Donald Thomson Collection is a testament to the rich cultural and economic lives of the Indigenous peoples of Australia and Papua, West Papua and the Solomon Islands.

In 2024, the University of Melbourne gained ownership of Thomson’s papers, journals, photographs and other materials and united them with the cultural materials collection.

The unity of the two collections after more than five decades, and the building of the Place for Indigenous Art and Culture, including the establishment of the Donald Thomson Collection Study Centre on the Parkville grounds of the University, provides an enormous opportunity to shed light on the treasure trove of cultural and biological material Thomson collected, through research to identify the specific details of his collecting activities.

With the object and literary collections united, researchers with an interest in the fields will have the opportunity for detailed studies, and, importantly for Aboriginal people from the communities of origin, detailed information about the people and places Thomson visited and what he collected will now be more readily available.

Politics & Society

‘Finding an Indigenous voice’

Finally, Aboriginal people will have a greater opportunity to identify cultural and biological material, and especially secret or sacred objects from their ancestors and communities that are subject to the Aboriginal Heritage Act of Victoria that recognises their ownership of this material and therefore their right to repatriation.

The significance of the Donald Thomson Collection for Aboriginal people today resides in its capacity to support cultural continuity and renewal.

Access to material culture is therefore especially important for communities of origin, especially when the significance of cultural material is enhanced by connecting with those for whom it has the most meaning and significance.

These are edited extracts from Dhoombak Goobgoowana – A history of Indigenous Australia and the University of Melbourne – Part 2: Voice, published by Melbourne University Publishing and edited by Dr Ross Jones, Dr James Waghorne and Professor Marcia Langton. Hard copies are available to purchase, and a free digital copy is available through an open-access portal.