When Australia met Un-Australia – film in the 2000s

Three films from the Film and Television archive show us what, and who, we were in the early years of this century

Published 7 June 2016

This article is the sixth in a series to mark the golden anniversary of Australia’s oldest film school, at the University of Melbourne’s Faculty of the Victorian College of the Arts and Melbourne Conservatorium of Music. The films embedded are among 50 by past students and today’s filmmakers, being made available to the public, for free, for the first time.

You go to the movies. Once, your friend took you to see The Fighter (2010) at some arty cinema down Lygon Street, and you said to her, “Why did I pay 18 bucks to see ferals in Braybrook?”, even though you knew they were American – your point was, the entire thing was plotless and depressing: the boxer, played by Mark Wahlberg, his half-brother, played by Christian Bale, their seven sisters with bad hair and teeth.

You go to the movies to get away from that sort of shit because you see it everyday: the triangles of factory roofs, the four gutted cars in every third house, the young mums doing their best with an $89 baby carrier strapped to their chests, a ciggie in one hand.

But, back in 2010, the audience in the cinema were loving The Fighter. They lapped up the sordid scenes and their four-dollar salted caramel choc tops. “His finest role,” said one when the film ended, meaning Christian Bale. To be honest, you preferred him as an American Psycho (2000).

It’s a shame the tops of Australian society are filled with the sort of people who see a film and think it’s a reflection of the state of a nation, then they go home and drink some pinot noir, and the next day make a policy about it. Policies that affect you, the Ordinary Australian ...

Or they get to talk on telly about their views on Australia and what makes it great, when half the time your normal person’s got no idea what those people are rabbiting on about. Where are the hardworking triumph stories they used to tell, like Spotswood (1992)?

The friend who took you to see The Fighter makes you watch three short Australian films with her because she’s writing about them for this website, as part of a series to mark 50 years of filmmaking at what she tells you is Australia’s longest-continuing film school, at the University of Melbourne’s Faculty of the Victorian College of the Arts and Melbourne Conservatorium of Music.

The bbq

You’re no film critic but you know that The BBQ (2007), by Shpend Mula, is supposed to be about good old-fashioned Australian values. An old woman and a younger man must have their cook-off, even as suspicious coppers drag their cowering neighbour from his home.

You think: How dare the forces of the government interrupt the Australian way of life, your inalienable right to roast lamb, your lawn-sets planted on neat green squares? This is your turf, you’ve gotta defend it! Why can’t politics and religion and those refugees keep out of our backyards? Farrrk. What a farce.

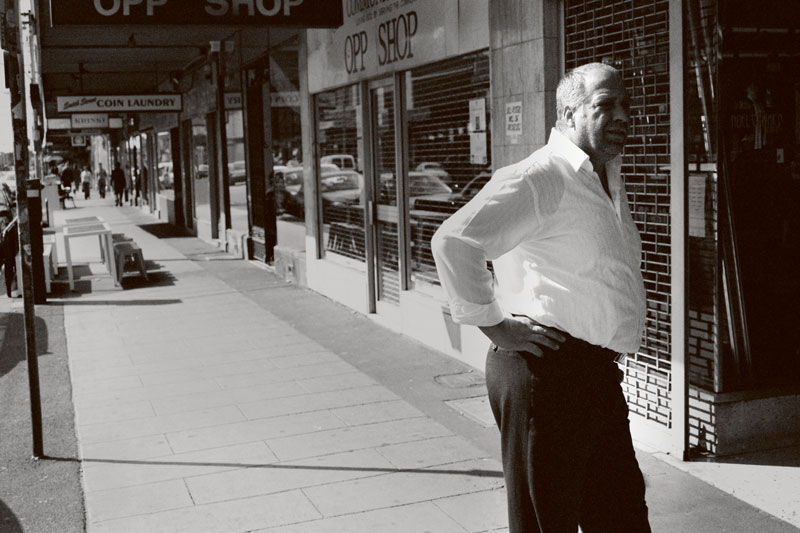

296 smith street

Meanwhile, on the other side of town, which might as well be a different part of the country, or a different country, because there is no country for old men who don’t speak English here, except the independent republics of their small businesses, you see a pawnbroker, Ahmed – the protagonist of John Evagora’s 2007 short, 296 Smith Street (2007).

At first, when you see Ahmed mark up his prices 300% you think: What a dodgy bastard. But then some deadbeat white guy who looks lazy-as keeps coming in and bugging him about a job, and some shonky Asian nicks off with a couple hundred bucks of Ahmed’s, the crook!

There’s a knife in Ahmed’s hand, not used for guaranteeing his place as “Man of Middle Eastern appearance” in the seven o’clock news but for peeling away stone to reveal comforting nubby shapes of small animals.

Scrape, scrape, scrape goes the knife, and you think about the robbery, and you think about the fat kid who comes into the shop and how Ahmed smiles at him but the kid’s mum drags him out of there in a flash, and scrape, scrape, scrape goes the knife, and you realise the man is just scraping by with his own wit and tolerance.

You look at your friend who is writing this article. Newspapers say she’s given them a glimpse into the window of multicultural Australia because she’s Southeast Asian and from a refugee background.

But you’ve known her for 30 years – you grew up together in the factory suburbs and you can sometimes see through the bullshit.

What a relief to suddenly be in the mainstream, to be a culture-maker, to be a “Brave new Australian Voice”, a label applied to her writing and no doubt to the work of these filmmakers.

But the shades on the windows come down when she thinks they will come knocking on her door with their sniffer dogs and batons and sirens, because her parents escaped that horror back home. Those folks thought Australia was supposed to be the lucky country, the safe country.

But what a sad relief for her that the reviled people have gone from being yellow to all shades of brown.

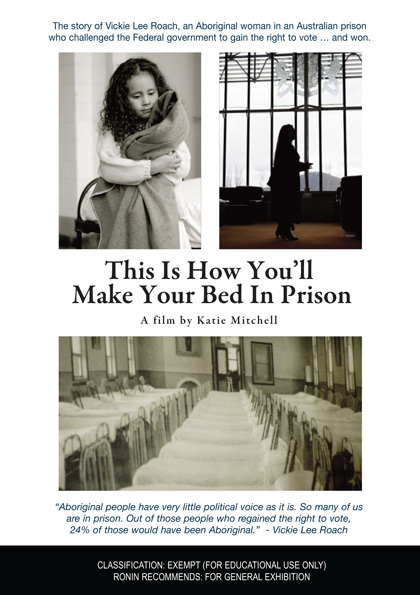

This is how you’ll make your bed in prison

“This is how you’ll make your bed in prison,” Vickie Lee says the youth shelter staff told her, in the 2009 short film of the same name by Katie Mitchell.

But Vickie is just a little girl at the time and not a crook. And you think: Some people are forgiven for small and large mistakes – private-school boys who knock letterboxes off their hinges or let air out of tyres. Even when they bash up homeless men, they still have lives left after jail time.

Your friend’s telling you that The BBQ is about “Un-Australian happenings” from our own backyards, 296 Smith Street looks at the lives of everyday Un-Australians, and This is How You’ll Make your Bed in Prison gives a voice to Un-Australian non-citizens who don’t deserve the right to vote.

There are too many “Un-Australians” in there, which you reckon makes for bad writing, but for ten years the government has given you this verbal pointed finger to direct at anyone you reckon fits the bill: “They’re hopeless, those Aborigines”. “They’re shifty, those ethnic pawnbrokers”. “They’re lazy welfare cheats, those bogans”. They’re all Un-Australian.

At the start of the 2000s, you had green and gold stars in your eyes, the Olympics were on your turf; but then a year later the Twin Towers fell and suddenly there was an Axis of Evil. So you pointed that finger to keep evil out of your country, only to have those ethnic Others come to you.

People you know

You like these three films, coz they show you people you know. Others might assume you aren’t cultured and only have dreams of making it big with your own McMansion, but they’re not the ones living next to and alongside the Ahmeds and Vickies. They’re safe in their inner-city suburbs while the “Un-Australians” get shoved with yous and you suppose that’s how 30-year old friendships are forged.

The media warned that the 2000s would begin with a major technological breakdown, but instead all you’ve seen are massive technological breakthroughs. You, the Ordinary Australian, are now connected to every kind of person in the world; but at the end of the decade, you realise that the stories closest to you are still the ones closest to home.

Banner image: Still from 296 Smith Street (2007) by John Evagora.

Alice Pung is a writer, lawyer and teacher. She was born in Footscray and grew up in Braybrook, attending local primary and secondary schools in the Western suburbs. The author of Her Father’s Daughter (2011) and Unpolished Gem (2006), and the editor of Growing up Asian in Australia (2008), Alice has received enormous critical acclaim for her writing. She graduated from the University of Melbourne in Law, LLB (Hons), and Arts (BA), in 2004.

This is the sixth article in a series to mark the Golden Anniversary of Film and Television at the Victorian College of the Arts. See Part One, Part Two, Part Three, Part Four, and Part Five. Visit the Film and Television 50th Anniversary website and Digital Archive website for more information.